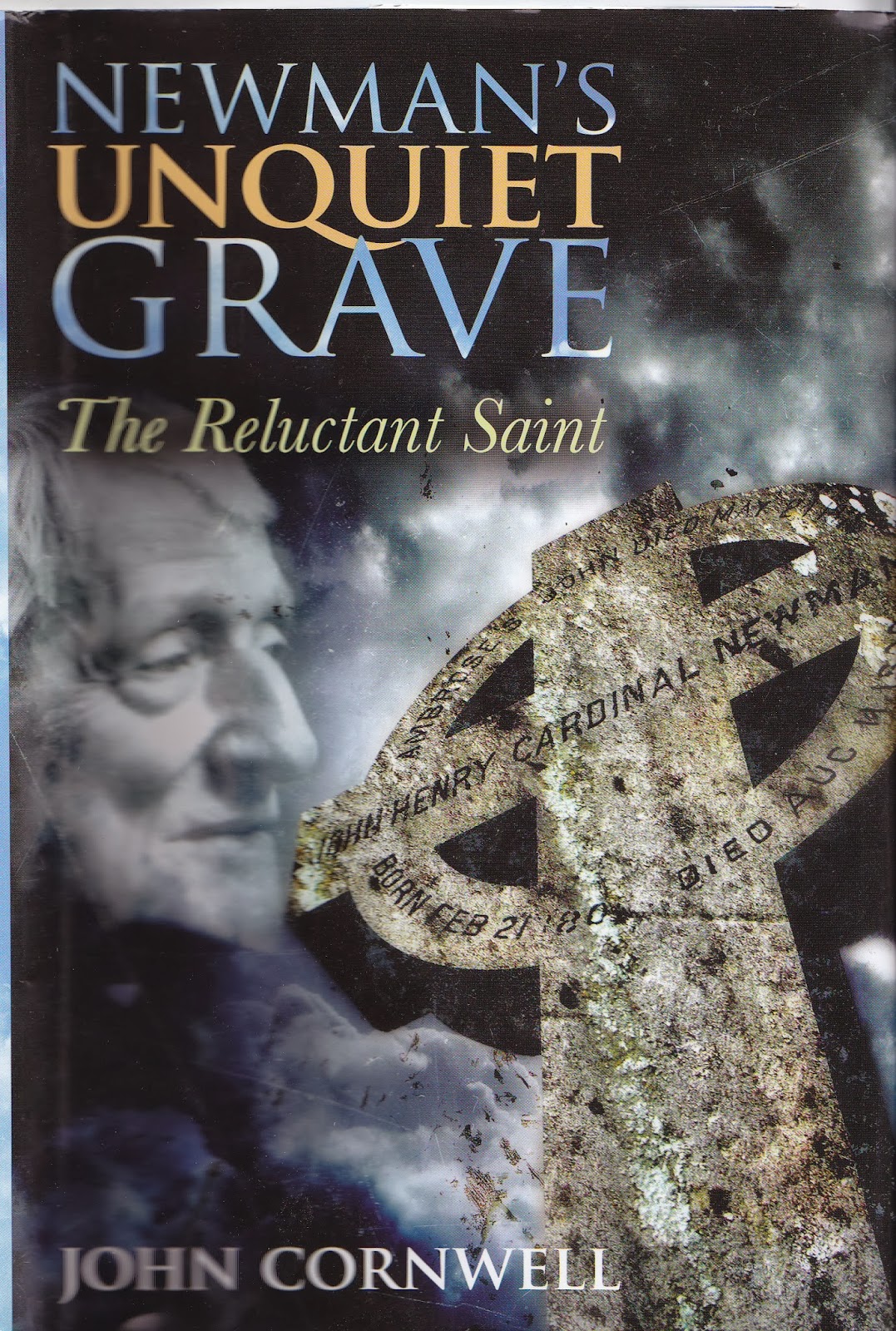

Having just read John Cornwell's biography of John Henry Newman, the Victorian theologian and prose stylist (much admired by James Joyce) I have been thinking about the ethics of biography. It used to be "scandal" of a heterosexual kind that exercised, if not biographers, then the climate of publicity around the publication of their books. Now the fun has switched to finding out whether or not the subject was homosexual. This immediately raises three questions for me: what business it it of ours? what standard of proof is required? and who cares?

When it comes to Newman (on the Catholic Church's long or shortlist for canonisation as a saint) the fact that he insisted on being buried in the same grave as his lifelong friend Ambrose St, John is enough for some, including my old friend, gay rights campaigner, Peter Tatchell. Peter may be right that Newman was gay but equally the relationship with Ambrose St John could have been a deep, affectionate same-sex friendship (Cornwell's view). The fact is that we don't know. These buttoned-up Victorians, it turns out, were very emotional people. They used the language of love to describe friendships and Cornwell shows how this was a feature also of the Romantic poets like Wordsworth and Coleridge. The world of the celibate priest is one that is closed to most of us. It is hard to imagine what it might mean and, at the end of the day, people's private sexuality, the ways they choose to come to terms with it or sublimate it, is their own. In the case of the Catholic Church, however, the terrible child sex abuse scandals committed by priests and monks mean that the question can't be left there. If celibacy doesn't work (assuming that is the reason for the scandals which, of course, also happen in the non-celibate world too) then the issue does need to be confronted. Personally, I am grateful for the delicate way that Cornwell handled this issue in his biography saying no more and no less than was warranted.

"A precondition for reading good books is not reading bad ones: for life is short" - Schopenhauer.

Monday, 17 February 2014

Saturday, 18 January 2014

Remembering Bruce Chatwin

Today is the 25th anniversary of the death of Bruce Chatwin and his former school, Marlborough College, was the venue for a two-day colloquium on the writer that kicked off yesterday with a lecture from me and today lectures from Jonathan Chatwin and Susannah Clapp. It was a great pleasure to witness the students (Marlborough is now fully co-educational) showing their enthusiasm for Chatwin and reading out extracts from him so well. I ran a short travel-writing workshop with a group of sixth formers (using a passage from The Songlines to spark discussion) and it is clear that his influence is still strong. His old friend Michael Cannon unveiled a memorial plaque to him and there was much discussion about how seriously to take claims that he had not enjoyed his schooldays. As someone pointed out, in the 1950s no one expected to enjoy their boarding school experience but today's Marlburians certainly seem to be very happy and lively. And I have my commemorative mug!

Tuesday, 10 December 2013

A Short View of Mandela

In 2001 my novel A Short Book About Love was published by Seren. This is chapter 23. We have read so much about Nelson Mandela in the last week. I wonder if fiction can offer anything to our thinking about this remarkable human being.

23.IT NEVER ENDS

HERE IS AN affecting tale of an eighty-year-old man who

has found love. Literature mocks the lustiness, the out of

sequence amours of the aged. Saucy old bugger, they say,

elbowing each other in the ribs. Ought to be past it at his age.

Love, it seems, becomes undignified with age. What was

splendid at twenty is an embarrassment at eighty. Could it be

that we have got this wrong?

Old men take many forms.They can be angry and belliger-

ent, crusty and difficult, bitter and tyrannical. They can be,

not to mince words, old gits. But they can also be – and isn't

this how we all want to end up? – mellow and ripe. After a life-

time of raging at the world (which is something one has little

choice but to do) there's something to be said for hanging up

one's boots, filling a pipe, and striking the pose of the ripened

sage, the man who's seen it all and won't see some of it again.

Just before one departs, a little wisdom, a little ripeness, a

hand run through the bin of yellow grain, a knowing knead-

ing between finger and thumb, the delivery of a verdict.

And of course, these precious characteristics are to be

applied to women too.

At the end of a life one can either regret the performance

or turn it over gratefully in one's mind. With health and

strength and a full belly and a seat in the sun it might be

possible to say: things aren't so bad. Things could be worse.

If the man or woman is a thinker there might even have been

the attainment of some wisdom – though that's a tricky

concept, for sometimes we need to be foolish. Wisdom can

involve playing safe. But there is a need – at some stage in a

life - to play with fire.

It is the man's eightieth birthday and he has surprised and

not surprised everyone by announcing that it is also to be his

wedding day. His children, holding a lunch in his honour

elsewhere, are informed. Moments later, they emerge from

their private dining-room singing a traditional wedding

song. For this is not the coldly formal world of wet roofs and

grey skies and suburban lawns. It is Africa. The bridegroom

(whose wife is twenty seven years younger) is a man of great

calm and dignity. He is not an old git. Because he is the

President of his country the newspapers are full of nuptial

excitement. His old enemies – who put him in jail, who

threatened him with the gallows, who made him live in a

solitary cell, who made him slop out toilet-buckets and hack

at stones in the hot sun – are now as excited as anyone. They

send him their congratulations. Have they remembered that

twenty seven years is the period they kept him on the prison

island? His new wife has given them a useful mnemonic

The President is a forgiving man. So forgiving and so

dignified and so apparently without hate that we call him a

saint. Which may be true, for saints are always flawed, their

goodness offset by the jagged frame of ordinary humanity.

His friend from the prison island tells the newspapers that

he was a man of great strength and determination and

courage and resolve. Playing chess with a cellmate he told

the warders to lock away the board at the end of the day. He

repeated the instruction at the end of the second day but

halfway through the third, his opponent conceded defeat.

He could not go on playing chess with this man of iron, this

man who could see from afar what he wanted and who

proceeded, not in rushed steps, not breathless, to obtain it.

Perhaps saints are difficult to live with. Perhaps the best

thing is to step aside and let them get on with it.

The cruel authorities sometimes pretended to be kind.

They offered their now famous prisoner better conditions.

They said he need not collect the buckets nor go out to the

quarry with his pick and shovel. But he refused, saying that

all were equal in that place. That is the sort of thing that

saints say. They are also human. The old man, in his younger

days, was a little vain. He refused to shave off his beard to

make himself more invisible to the police and the sentries at

roadblocks because he was attached to his magnificent

fungus. Pictures of him appeared on the walls of student

digs and inner city squats and the beard was always there as

it was always there in the pictures of Che Guevara. But Che

was a Latin with a black beret and his beard was straggly and

romantic.

So let us leave the old man on his birthday/wedding day,

walking in the hot African sun, smiling among the crowds,

thinking to himself, perhaps, that the air is good and that it

is not such a bad idea, all things considered, to be alive.

Extract from A Short Book About Love (Seren, 2001) by Nicholas Murray

Monday, 18 November 2013

Rip Van Winkle Awakes to a Brave New World

Copious apologies to readers of this blog who have noticed a word-famine or long sleep over the past couple of months. I have been very busy and writing entries to my blog has rather fallen by the wayside. I fully intend to wake up and get scribbling but in the meantime here is a link to my other blog which I write as publisher of the small poetry imprint, Rack Press. It's a tale of small publishers and big giants and I make the link between the effortless power of Amazon and Huxley's Brave New World. Huxley, of course, died 50 years ago this week on the very day of the Kennedy assassination as those of you who caught me talking last Tuesday on BBC Radio 4 about him will know. That programme by the way can be downloaded as a podcast ("A Brave New World", Radio 4) because it is a Radio 4 Documentary of the Week.

Tuesday, 3 September 2013

Huxley in Oxford: The Condemned Playground

|

| Peter Wood from New York addresses a session on Huxley's ideas in teaching |

The conference incorporated the Fifth International Aldous Huxley Symposium and I attended a forum as part of the latter called Aldous Huxley and a New Generation of Readers which had fascinating contributions from Swiss, American and Singaporian teachers about how Huxley's texts and indeed his ideas about teaching and learning are being used and applied in contemporary schools and colleges. Robin Hull, a Zurich private school headteacher, reported that a majority of his 15 year olds in a survey said they thought Brave New World was relevant to them and meant something, which I feel is encouraging.

The conference also heard an informal and amusing talk from Evelyn Waugh's grandson, Alexander Waugh, about the current project to publish a full edition of Waugh's letters. To judge from the extracts he shared this will be something to look out for.

Monday, 26 August 2013

Do People Still Buy Poetry?

|

| Charlotte Mew |

All poetry publishers, great and small, have been finding that sales are dropping though it is worth reminding ourselves that there never has been a golden age. I used to admire the volumes in the Oxford University Press list in the 1970s and 1980s but I was told recently that the actual sales figures were surprisingly low. I am reading at the moment the Collected Poems of Charlotte Mew published by Gerald Duckworth in 1953. In the introduction by Alida Munro, wife of the Poetry Bookshop proprietor Harold Monro, she reveals that, exceptionally, 500 copies of Mew's debut collection The Farmer's Bride were published in 1929 when the Poetry Bookshop's normal print run was 250. The Poetry Bookshop (and I have written elsewhere about this in my The Red Sweet Wine of Youth: The British Poets of the First World War and more recently Matthew Hollis has covered similar ground in his biography of Edward Thomas) was at the centre of British poetry in the years just before and during the First World War. Anyone who cared about the future of poetry would know that the Imagists and Georgians championed by Monro were where it was at. The history of modern poetry has confirmed this but...250 copies.

It sometimes feels that the poetry readership is finite, that all the marketing and tweeting in the world won't get it into four figures for a new book, but that can't be accepted passively so what do we do? Is it that people are lazy and can't make the effort of special attention that poetry needs to yield up its pleasures? I don't think we should blame the readers. I would offer two explanations. The first is that we lack proper criticism. Strong, reliable, discriminating reviewers and critics (not eloquent puffs from the poet's friends masquerading as a book review) could help sort out the wheat from the chaff. I believe (maybe because I can't face the consequences of not believing) that if people are put in touch with the very best poetry being written they will buy it and read it as they still do, to some extent, in the case of quality literary fiction. But reviewing just now is partial, selective, lacking in critical authority and doesn't even perform the basic function of telling us what has come out. Excellent new books of poetry sometimes receive no reviews at all. So unless you happen to be lucky enough to stumble on one of those books they remain silent phantoms in a warehouse or on the poet's Mum's mantlepiece. Some form of comprehensive monthly listing with short reviews would enable us at least to know what was out there.

Secondly, we need to improve the marketing and distribution of poetry, to get it into the bookshops. Booksellers like Foyles need to wake up and start stocking small press poetry for starters. The funds of the Arts Council for England, Literature Wales etc need to be used to set up some sort of network for small poetry presses, a kind of affordable Inpress that you didn't have to pay to join that was the equivalent of Italian olive growers banding together as co-operatives to market their produce. A pilot project, some hard-headed research, some practical scheme for helping poets and their readers get in touch with each other, would be far more helpful than individual grants to poets.

In the end if the poetry being offered to readers is no good then they can't be blamed for declining to sample it but I believe that there is enough decent poetry being published to tempt them if they can be enabled to locate it. Otherwise poetry will die from neglect. And that, we can all agree, is unthinkable.

Monday, 29 July 2013

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)