"A precondition for reading good books is not reading bad ones: for life is short" - Schopenhauer.

Wednesday, 10 December 2014

Meeting a Poem Again

I was surprised and, as they say on Facebook, delighted (or is it 'thrilled'?) to learn last night that a poem that appeared first in the Times Literary Supplement in 1986 has been chosen as Poem of the Week on the TLS website this week. It was the TLS that published my very first poem back in 1981 and I well recall that, having forgotten to tell me that they had accepted it for publication, the proof dropped through my letterbox in a brown envelope one Saturday morning. I don't think there will ever be another morning surprise quite like that one. The poem was chosen by TLS poetry reviewer Andrew McCulloch who explains his choice on the website. It is reprinted in my collection, Acapulco: New and Selected Poems (Melos) and you can buy that volume direct from Melos online.

Monday, 17 November 2014

Innovation-lite

This year's £10, 000 Goldsmiths prize "set up to recognise fiction that opens up new possibilities for the novel form" as The Guardian puts it, has just been won by Ali Smith for her novel How to be Both. The previous year, the first of this particular prize, it was won by Eimear McBride for A Girl is a Half-formed Thing. McBride's novel was originally published by a small press in Norfolk, Galley Beggar Press, and allegedly took nine years to find a publisher. It has been re-issued by Faber (who presumably had turned it down during that nine year search) and, in spite of its radical formal qualities (essentially a technique of fractured syntax) that might be thought off-putting to the general it appears to be selling very well.

The Poetry Society also has an award which looks as though it is designed to foster innovation, the Ted Hughes Award for new work in poetry which says that it is looking for the poet who has made "the most exciting contribution to poetry this year". In the words of one of this year's judges, Kei Miller:

In a broadly sympathetic review of McBride's novel in the New York Review of Books Fintan O'Toole observed that: "The originality of this method has been greatly overstated – a mark perhaps of how far the mainstream of fiction has drifted from the modernist aesthetic." He seems to be saying that most current fiction is "conventional" so any attempt to dislocate the form starts to look bold and dangerous. He goes on to say that: "McBride's gamble with the reader is that we will form meaning even when she does not quite give it to us." This accurately describes my experience in reading the book. I confess that the method nearly made me stop reading but I was eventually hooked by the compelling power of the story and 'got used to' the formal innovation which perhaps wasn't quite how it should have been. The story (of childhood rape, a life of casual self-hating sexual encounters on waste ground, the dysfunctional family) was of course just the sort of underclass fable the metropolitan literati loves to read, innovation or no innovation.

I have forgotten who it was who said of experimental writing that the experiment should be over by the time we are invited to read it but I have some sympathy with that idea. Words like 'experimental', 'avant-garde', 'left-field' are often tendered in a spirit of self-satisfied defiance. Too many suburban Rimbauds are too quickly pleased with their ground-breaking attempts. Too many currently vaunted 'modernist' novels simply cannot be weighed in the same scale as Joyce. The assumption that writing that does not proclaim its innovatory qualities is conservative, traditional, conventional etc etc in my view doesn't follow. Such limp writing does exist and I am not advocating it but equally the innovation-lite works don't always strike me as an improvement on the jejeune traditionalists.

Which brings me back to the comment of Julia Copus about new work that "leaves me more keen-sighted, able to see the world newly and distinctly". That seems to me the real 'innovation' that formal experiments are there to enact. Any artist, in words, music, paint, film, is trying to produce something creative and original which is literally innovative because it makes something new that was not there before. It makes us see, feel, hear in fresh ways. There should be no prizes for innovation; there should simply be genuinely new work.

The Poetry Society also has an award which looks as though it is designed to foster innovation, the Ted Hughes Award for new work in poetry which says that it is looking for the poet who has made "the most exciting contribution to poetry this year". In the words of one of this year's judges, Kei Miller:

"It’s hard to say what I would look for in terms of ‘innovation’. A lot of things are conventionally innovative – a bit of multimedia, a bit of hyperlinks thrown in. Perhaps then I’m just looking to be surprised, in a good way, and by something that accentuates the poetry rather than detracting from it. So much is available to us today – not just technology, but everything in the material world. The truly innovative poet will know how to choose carefully. That’s I’m looking for – careful choices, surprising choices, smart choices."I must say I like the relaxed tone of this, its recognition that innovation comes in all shapes and sizes. Another judge, Julia Copus, says she is looking for work that "leaves me more keen-sighted, able to see the world newly and distinctly". But isn't that what most of us thought any work of art in any medium was trying to do?

In a broadly sympathetic review of McBride's novel in the New York Review of Books Fintan O'Toole observed that: "The originality of this method has been greatly overstated – a mark perhaps of how far the mainstream of fiction has drifted from the modernist aesthetic." He seems to be saying that most current fiction is "conventional" so any attempt to dislocate the form starts to look bold and dangerous. He goes on to say that: "McBride's gamble with the reader is that we will form meaning even when she does not quite give it to us." This accurately describes my experience in reading the book. I confess that the method nearly made me stop reading but I was eventually hooked by the compelling power of the story and 'got used to' the formal innovation which perhaps wasn't quite how it should have been. The story (of childhood rape, a life of casual self-hating sexual encounters on waste ground, the dysfunctional family) was of course just the sort of underclass fable the metropolitan literati loves to read, innovation or no innovation.

I have forgotten who it was who said of experimental writing that the experiment should be over by the time we are invited to read it but I have some sympathy with that idea. Words like 'experimental', 'avant-garde', 'left-field' are often tendered in a spirit of self-satisfied defiance. Too many suburban Rimbauds are too quickly pleased with their ground-breaking attempts. Too many currently vaunted 'modernist' novels simply cannot be weighed in the same scale as Joyce. The assumption that writing that does not proclaim its innovatory qualities is conservative, traditional, conventional etc etc in my view doesn't follow. Such limp writing does exist and I am not advocating it but equally the innovation-lite works don't always strike me as an improvement on the jejeune traditionalists.

Which brings me back to the comment of Julia Copus about new work that "leaves me more keen-sighted, able to see the world newly and distinctly". That seems to me the real 'innovation' that formal experiments are there to enact. Any artist, in words, music, paint, film, is trying to produce something creative and original which is literally innovative because it makes something new that was not there before. It makes us see, feel, hear in fresh ways. There should be no prizes for innovation; there should simply be genuinely new work.

Monday, 3 November 2014

Pelmeni Poets 2nd December: Come Along!

The Pelmeni Poetry Series

Please join us for the sixth in this series of poetry readings

on

Tuesday 2nd December, 2014

at

The Duke of Wellington

119 Balls Pond Road

London N1 4BL

020 7275 7640

6.30pm for 7.00pm

http://www.thedukeofwellingtonn1.com/how-to-find-us/

Featuring the work of

Eve Grubin, Kathryn Maris, Nicholas Murray and Chrissy Williams

Plus Special Guests from Pelmenis Past!

Pelmeni Poetry aims to bring together poets from the US, South America,

Europe, Asia, Africa and the Middle East to audiences in London, hosting

the best international voices and visions at a variety of venues in the city.

Wednesday, 22 October 2014

Dylan Thomas, like, wow, could write!

Strolling through Bloomsbury today what should I see, parked in a piece of open space on the very cusp of Fitzrovia, but Dylan Thomas's writing shed. Except that, er, it wasn't. It was a faithful reproduction that is being towed around these islands, having started out of course in Wales where I should have caught up with it before. It is being called The Pop-up Writing Shed and inside (I learned when I read the handout after I had left the scene) visitors were being asked, "in honour of Dylan Thomas' love of words" to help to compile a dictionary of fresh new words. "Be playful," the Shed's curators say, "be rhythmic, be onomatopoeic, be brave". Had I noticed this option I think I would have posted to the projected Dictionary of Dylan the word "shamshed". Instead I pottered amongst the reproductions of letters, photographs, and what may have been actual books from his boathouse.

Strolling through Bloomsbury today what should I see, parked in a piece of open space on the very cusp of Fitzrovia, but Dylan Thomas's writing shed. Except that, er, it wasn't. It was a faithful reproduction that is being towed around these islands, having started out of course in Wales where I should have caught up with it before. It is being called The Pop-up Writing Shed and inside (I learned when I read the handout after I had left the scene) visitors were being asked, "in honour of Dylan Thomas' love of words" to help to compile a dictionary of fresh new words. "Be playful," the Shed's curators say, "be rhythmic, be onomatopoeic, be brave". Had I noticed this option I think I would have posted to the projected Dictionary of Dylan the word "shamshed". Instead I pottered amongst the reproductions of letters, photographs, and what may have been actual books from his boathouse. It was very popular and it was soon difficult to turn round in the small space for fear of treading on eager poetry, or at any rate, Dylan lovers. One woman expressed astonishment at the sight of his neat, legible handwriting on a letter spread out on the table. "That's amazing, I didn't think he would write so clearly if he was drunk all the time." I scanned her face for signs of irony but no, this is what she genuinely believed. "Perhaps he had an old-fashioned Welsh education, taught how to write in pen and ink," I offered primly. This earned me an old-fashioned look. It's true that I may not have been careful enough in my perusal of the shamshed, but I couldn't see any poetic manuscripts about. But in a sense that's not the point. DT is the point. He is, as Cliff Richard said of Elvis "a phenomena". He is popular, unlike most poets, so let's not carp. And if you are in Fitzrovia this weekend there's a special "Dylan Thomas in Fitzrovia" festival which should be a lot of fun. But get to the shamshed early before it's crowded out.

Monday, 13 October 2014

War, war

I am looking forward to taking part with some other writers and anthologists in an event on the First World War at the Working Men's College in Camden organised by Lucy Popescu on Thursday 6 November. I won't actually be talking about my book on the war poets (illustrated here) but will be reading Trench Feet my verse satire on an academic who decides to turn the clichés of the Great War into a TV career opportunity and comes badly unstuck. I am also talking, but this time about the more serious book, at the Special Forces club on Monday 10th November and I have a forthcoming review in the Times Literary Supplement on some recent books of war poetry.

Wednesday, 8 October 2014

Brave New Worlds

I hugely enjoyed giving a talk last Friday (10 October) at the Cheltenham Festival of Literature on Aldous Huxley's Brave New World. I was arguing that his 1932 novel is still highly relevant to current political and cultural debates, but I also was looking at its specific historical moment, at where it came from, at what made Huxley write it. It was an excellent Cheltenham audience with some very interesting an intelligent questions.

Friday, 19 September 2014

Satirical Poetry: More Please!

Satirical poetry is relatively thin on the ground just now – it can hardly be for lack of provocation – but I have found that my own attempts have been sufficiently well received to make me think that it is worth more writers having a go. I have tended to think that it works best when using relatively formal metres but of course that isn't a hard and fast rule. My satire (or do I mean diatribe?) against the Coalition Government, Get Real!, published by Rack Press in 2011 used the very satisfying form perfected by Burns and my most recent one, Trench Feet, also from Rack Press earlier this year, has just earned some kind words from the Poetry Book Society selectors.

Satirical poetry is relatively thin on the ground just now – it can hardly be for lack of provocation – but I have found that my own attempts have been sufficiently well received to make me think that it is worth more writers having a go. I have tended to think that it works best when using relatively formal metres but of course that isn't a hard and fast rule. My satire (or do I mean diatribe?) against the Coalition Government, Get Real!, published by Rack Press in 2011 used the very satisfying form perfected by Burns and my most recent one, Trench Feet, also from Rack Press earlier this year, has just earned some kind words from the Poetry Book Society selectors. The PBS pamphlet choice for this quarter is Holly Hopkins' Soon Every House Will Have One (Smith/Doorstop) but they singled out several runners-up, including Trench Feet about which they wrote in the new PBS Bulletin: "After Get Real!, Murray's 2011 pamphlet satirising the Coalition Government, he now turns his attention to the celebrations of the centenary of the First World War. Here bright, ambitious academic Jeremy Button, is commissioned to make a TV series focusing on the War Poets, but things do not go according to plan in this witty and erudite lampoon." I should say that the wildly exaggerated scenes satirising a London literary prize-giving party are drawn from life but, no, I am not going to tell you where and when!

Get Real! is out of print as a pamphlet but the full text is in my Acapulco: New and Selected Poems (Melos Press) and it can be ordered online from Melos. Trench Feet is still in print and can be ordered online from Rack Press or from poetry-loving bookshops like the London Review Bookshop in London or Foyle's.

Wednesday, 17 September 2014

Mass Escape from the Zoo!!!

What is happening? The thunder of animal hooves rushing down the gangplank from the Ark is being heard everywhere. Ted Hughes's Bestiary just published is only the latest in a surge of animal poem collections. I have even contributed to it myself. Pascale Petit's Fauverie from Seren containing poems sparked by the Paris zoo, John Burnside's latest collection, poets in residence at London Zoo, workshops on animal writing...where will it end? It is good, I suppose, that we are all being tender towards our fellow creatures on this planet.

My collection of animal poems (pictured here) can be ordered online from Melos.

My collection of animal poems (pictured here) can be ordered online from Melos.

Monday, 8 September 2014

War, Jaw and Grub Street Revisited

|

| Just about to enter the sacred cloister at Wadham |

These thoughts occurred to me yesterday as I dipped through the mediaeval portal of Wadham College, Oxford, to deliver a paper at the English Association conference on British Poetry of the First World War. My subject was "How 'Anti-War' were the War Poets?" and I argued for 20 minutes that the received wisdom that the poets of WW1 were 'anti-war' was not a piece of wisdom at all and that only the true pacifists could lay claim to that label. I see Owen and Sassoon (decorated soldiers who pressed to go back to the front) as more 'anti-heroic' in their writing than 'anti-war'.

My audience unexpectedly (for me) included the poet Michael Longley whose new collection, The Stairwell, from Cape I had just read. It was a great pleasure to meet him and to hear him tell the hall he liked my paper. Everything was charming and well-mannered with not a hint of odium anywhere and my nervousness (even as the author of a book on the subject of WW1 poetry) at addressing the scholars soon vanished. In subsequent sessions, however, I discovered that Jeremy Paxman was not in such a favoured position and was honorary bogeyman of the day. Absent also was the terrible theoretical jargon (the awful intellectual puns that made one wince, the turgid half-digested philosophy from Eng. Lit. academics not trained in philosophical discourse) of a decade or so ago. Everyone is speaking plain English again and I could understand every word. "I know, too, how apt the dear place is to be sniffy," Matthew Arnold said of Oxford in the 19th Century but it certainly wasn't yesterday. In fact Grub Street (as represented in my latest verse satire, Trench Feet) is more likely to be snobbish and 'sniffy', with more cold-shoulders in the average literary or publishing party in London than in this gathering of friendly and communicative academics and teachers.

During the delivery of my paper I kept hearing a frantic buzzing vibration in my pocket from my silenced mobile phone. Later I discovered that people had been tweeting my argument as it unfolded. I hope it didn't diminish their attention. In fact it was the Grub Street Irregulars like me who seemed to lack the audio-visual flair and I felt rather old-fashioned arriving without memory stick Power Point or handout and relying on words alone.

The conference concluded with a panel on "The Historians v. The Poets" where the consensus seemed to be that this was a phoney war and that the alleged distorting effects on public consciousness of poetic representations of it were unproven and that both poetry and history were legitimate ways of exploring what happened. Someone suggested from the floor that poets and historians should make common cause against the real culprits: the politicians who got everyone into this mess in the first place.

Saturday, 23 August 2014

Presteigne Festival: The Welsh Poets of the Great War

|

| Nicholas Murray outside Norton Church, Thursday 21 August |

Rhyfel (War):

Bitter to live in times like these.

While God declines beyond the seas;

Instead, man, king or peasantry,

Raises his gross authority.

While God declines beyond the seas;

Instead, man, king or peasantry,

Raises his gross authority.

When he thinks God has gone away

Man takes up his sword to slay

His brother; we can hear death's roar.

It shadows the hovels of the poor.

Man takes up his sword to slay

His brother; we can hear death's roar.

It shadows the hovels of the poor.

Like the old songs they left behind,

We hung our harps in the willows again.

Ballads of boys blow on the wind,

Their blood is mingled with the rain.

We hung our harps in the willows again.

Ballads of boys blow on the wind,

Their blood is mingled with the rain.

Hedd Wyn [translated by Gillian Clarke]

Thursday, 19 June 2014

Bloomsbury and the Poets

Today is publication day of Bloomsbury and the Poets, the first title in a prospective series of prose books from the new imprint Rack Press Editions. It is a short book about the poets who have lived in Bloomsbury and, as you might imagine, there are plenty of these. You can obtain the book directly from the Rack Press website at a discounted price of £6 rather than the full price of £8.

This morning the TLS diary has an item on the book by the inimitable JC who mentions that a few details (unsurprisingly) were familiar to him from my earlier book Real Bloomsbury. Actually there is a great deal of new material including much more on Bloomsbury's major woman poet, Charlotte Mew.

This morning the TLS diary has an item on the book by the inimitable JC who mentions that a few details (unsurprisingly) were familiar to him from my earlier book Real Bloomsbury. Actually there is a great deal of new material including much more on Bloomsbury's major woman poet, Charlotte Mew.

|

| Times Literary Supplement, 20 June 2014 |

Wednesday, 18 June 2014

Thank You is the Hardest Word

Just back from my annual visit to Greece I was struck by the number of times I heard people say, in English, "thank you". It must be the current fad, like people saluting each other in trendy wine bars with "Ciao!" I didn't just hear it in cities but also, for example, in a tiny Dodecanese island where someone had just lifted a woman's push-chair over an obstacle at the entrance to the church where a local festival was going on. It's ironic that this comes at a time when the word, rather like "please", is going out of fashion in the country of its origin. No one under the age of 25 says any more: "Please can I have a coffee" but "Can I get a coffee", if my controlled scientific observation of three people in the queue in front of me at Paddington station can be accepted as legitimate data.

I recently had a letter from a well-known journalist and writer to whom I had sent, unsolicited, a copy of my recent satirical poem, Trench Feet, published in April by Rack Press. He didn't know me and I didn't know him but since my satire on the current WW1 media clichés chimed with a recent polemical piece he had written in a national newspaper I thought he might be interested. He had gone to the trouble of writing an actual letter to someone he had never met. It reminded me that nearly everyone else to whom I had sent the poem (except those who bought a copy and who later wrote to me in uncharacteristically large numbers, i.e more than five) had maintained an impeccable silence. Were they right to do so? After all, an unsolicited gift is like internet spam, there is no obligation to pay it any heed. We no longer live in an Edwardian world of formal manners. And why was I doing it? Soliciting some free praise that I could paste on the cover of future editions? Fishing for compliments? Advertising my self-importance? I think it was none of these. I just thought that some people I knew would be interested. It's a bit like returning someone's smile in the street as you nearly collide. It's what people used to do. It's called human communication. It's a social medium.

It's actually very easy to deal with this sort of thing by using any of a number of ready-made phrases like: "Thanks for this, I look forward to reading it," which doesn't commit you to saying anything once that promised reading has happened, if it ever does happen. You don't even have to reveal the fact that you sense you are going to loathe it. You have acknowledged your friend/acquaintance's gesture and that is enough. You are not obliged to like anything your friend has written. Instead, I was greeted by silence from the sort of people who spend hours every day tweeting and posting and blogging on social media. All that scribbling and commenting, it seems, leaves no time for a simple "thank you" (in English or Greek). Life is too short; we are all too busy...Here's a picture of my dog eating a copy of the Guardian Review. Likes (47)

What would I do in such circumstances? Surely a quick email or card? I hope so, and this has made me more determined than ever to make sure that I remember to respond to anyone who sends me anything as a personal gift, because I am sure I have forgotten to do so on occasion. A reminder of which occasion exactly: that is definitely something that would send a tremor through someone's tweeting arm.

ευχαριστώ!

ευχαριστώ!

Tuesday, 13 May 2014

The Writing Process

I have been asked to answer four questions so here goes!

What are you working on?

Like most writers I always have more than one project on the go but my main effort at the moment is going into work on a new poetry collection called "Facing the Facts" (the title poem arrived and immediately decided to start calling the shots). Then I am actively revising a novel that came close to being published a few years ago. Revisiting it I realised that it was far better than I thought (even the rejection letter was the best I've ever had) so I am feeling quite positive about it. I think I know what needs to be done. Next month I am publishing a (very) short book called Bloomsbury and the Poets, and another potentially big non-fiction project is, as they say, "being discussed".

In the extraordinarily difficult climate in British publishing just now I would like to announce a commission to write a new literary biography but I am unable to do so even though I still very much see myself as a literary biographer, confirmed by two invitations this week to talk about one of my subjects, Aldous Huxley. I am being interviewed about him by the BBC on Wednesday for a documentary being made by Francine Stock and I have been asked to take part in a panel on literary dystopias at the Cheltenham Festival of Literature in October.

How does your work differ from others of its genre?

I think that my biographies are not wildly different from the current norms of the genre. I pay particular attention to the literary quality of the biography as a piece of writing rather than its being just a decent research-effort, but the best ones always do that. Poetry by its nature is unpredictable, innovative, surprising, so it will always be chafing against the constraints of genre but it is not for me to say how original my poetry is. I think it is in my fiction that I have tended to depart from genre norms as I love books that mix all sorts of things together in free-associating ways. That is probably why I am not a best-selling novelist! Overall I don't like the constraints of genre. Last year I completed a short dystopian novel. I sent it to A Very Prestigious Literary Publisher & Co who replied that it was very well-written and full of good things but they couldn't possible touch it because it was Genre. I then sent it to a publisher known to be friendly towards the genre of future fiction and they replied that it was very well-written and full of good things but they couldn't possible touch it because it was "too literary". I then tapped my head slowly against the wall howling gently.

Genre, box-ticking, pigeon-holing, are the marketing vices of our contemporary risk-averse publishing scene. [ugly sound of a raspberry being blown]

Why do you write what you do?

I write because I have to. It is a visceral inner compulsion, a need, not a decision or a career choice. It is a vocation and I simply can't remember a time since I was a child making up newspapers with my sister when I haven't been writing. I was, however, a late developer when it came to publishing and my first book didn't appear until I was 40. I have more than made up since for lost time! I write poetry because poems, as Larkin famously said, "turn up". I have no choice in the matter. I love prose also, nonfictional and fictional. I love words and doing things with them, I love their patterns and I love the spaces between words, the echoes and the music, the suggestiveness, the possibilities. I write biographies because I am interested in other people's lives and how they are shaped. Writing is a pleasure (and the pain in the end must be part of the pleasure) that is almost equal to the sublime pleasure of reading. "Good readers," Borges observed, "are rarer and blacker swans than good writers." Reading is a great creative act that nourishes, that makes writers what they are.

How does your writing process work?

That is a hard question. I have regular, disciplined habits. I write best early in the morning when the day and I are both fresh and I write quickly and fluently. I have no idea what writer's block could possibly be about. But if I have learned anything from experience – and I did not learn this early enough – it is that revision is vital. All writing is re-writing someone said and I agree. Those first rapid brushstrokes can sometimes turn out to be crooked and misapplied. Try and try again. I don't need a special place to write and can do it anywhere. I can write if there is a pneumatic drill going on underneath me but I must have no interruption. Total concentration, a locked door, an empty room, no visitors, callers, well-wishers, and I can write, lost utterly in the process of composition. But an interruption is a catastrophe.

Ping! It looks as though someone has pressed the buzzer. I must now get off the bus and let the tour continue...

In the extraordinarily difficult climate in British publishing just now I would like to announce a commission to write a new literary biography but I am unable to do so even though I still very much see myself as a literary biographer, confirmed by two invitations this week to talk about one of my subjects, Aldous Huxley. I am being interviewed about him by the BBC on Wednesday for a documentary being made by Francine Stock and I have been asked to take part in a panel on literary dystopias at the Cheltenham Festival of Literature in October.

How does your work differ from others of its genre?

I think that my biographies are not wildly different from the current norms of the genre. I pay particular attention to the literary quality of the biography as a piece of writing rather than its being just a decent research-effort, but the best ones always do that. Poetry by its nature is unpredictable, innovative, surprising, so it will always be chafing against the constraints of genre but it is not for me to say how original my poetry is. I think it is in my fiction that I have tended to depart from genre norms as I love books that mix all sorts of things together in free-associating ways. That is probably why I am not a best-selling novelist! Overall I don't like the constraints of genre. Last year I completed a short dystopian novel. I sent it to A Very Prestigious Literary Publisher & Co who replied that it was very well-written and full of good things but they couldn't possible touch it because it was Genre. I then sent it to a publisher known to be friendly towards the genre of future fiction and they replied that it was very well-written and full of good things but they couldn't possible touch it because it was "too literary". I then tapped my head slowly against the wall howling gently.

Genre, box-ticking, pigeon-holing, are the marketing vices of our contemporary risk-averse publishing scene. [ugly sound of a raspberry being blown]

Why do you write what you do?

I write because I have to. It is a visceral inner compulsion, a need, not a decision or a career choice. It is a vocation and I simply can't remember a time since I was a child making up newspapers with my sister when I haven't been writing. I was, however, a late developer when it came to publishing and my first book didn't appear until I was 40. I have more than made up since for lost time! I write poetry because poems, as Larkin famously said, "turn up". I have no choice in the matter. I love prose also, nonfictional and fictional. I love words and doing things with them, I love their patterns and I love the spaces between words, the echoes and the music, the suggestiveness, the possibilities. I write biographies because I am interested in other people's lives and how they are shaped. Writing is a pleasure (and the pain in the end must be part of the pleasure) that is almost equal to the sublime pleasure of reading. "Good readers," Borges observed, "are rarer and blacker swans than good writers." Reading is a great creative act that nourishes, that makes writers what they are.

How does your writing process work?

That is a hard question. I have regular, disciplined habits. I write best early in the morning when the day and I are both fresh and I write quickly and fluently. I have no idea what writer's block could possibly be about. But if I have learned anything from experience – and I did not learn this early enough – it is that revision is vital. All writing is re-writing someone said and I agree. Those first rapid brushstrokes can sometimes turn out to be crooked and misapplied. Try and try again. I don't need a special place to write and can do it anywhere. I can write if there is a pneumatic drill going on underneath me but I must have no interruption. Total concentration, a locked door, an empty room, no visitors, callers, well-wishers, and I can write, lost utterly in the process of composition. But an interruption is a catastrophe.

Ping! It looks as though someone has pressed the buzzer. I must now get off the bus and let the tour continue...

Monday, 24 March 2014

Roy Jenkins and I

It is more than 12 years since I received this letter out of the blue from Roy Jenkins who is now being much talked of as a result of a new biography by John Campbell. I am still slightly amazed.

Writing About the Great War

|

| Ford Madox Ford |

Next month my satirical poem, Trench Feet (Rack Press) about an ambitious TV academic who sees the centenary as an opportunity to make a name for himself by reshuffling the standard clichés about the War (and who comes badly unstuck) will be published and naturally I have been thinking about how we should represent this event. Having been commissioned, as the author of a book about the war poets, The Red Sweet Wine of Youth: British Poets of the First World War (Abacus), to give several talks during the year, I have been reflecting on two issues: how the participant writers represented the conflict and how (largely as a result of those representations) it is seen today. The second of these is for another day but as Tim Kendall in his excellent new anthology of the poets puts it, the poets "have determined the ways in which the War has been remembered and mythologized. Not since the the Siege of Troy has a conflict been so closely defined by the poetry that it inspired."

Not just the poets. I am currently reading with great interest a collection of writings about the War by Ford Madox Ford, whose Parade's End tetralogy is one of the major fictional attempts to reflect the War in all its complexity. The collection, War Prose, edited by Ford scholar Max Saunders, brings together a lot of miscellaneous pieces by Ford and I strongly recommend it as a prophylactic against the routine clichés.

It is fascinating to witness Ford struggling to articulate his feelings about his experience and about the problem of rendering those feelings, and the conflict itself, with any semblance of accuracy. His 1916 essay "A Day of Battle" begins: "I have asked myself continuously why I can write nothing – why I cannot even think of anything that to myself seems worth thinking! – about the psychology of that Active Service of which I have seen my share. And why cannot I even evoke pictures of the Somme or the flat lands round Ploegsteert?" He considers his writerly powers of visualisation that have been praised by others yet which in this instance desert him. He finds "the mind stops dead, and something in the brain stops and shuts down". The experience was so extraordinary that it defeated him: "As far as I am concerned an invisible barrier in my brain seems to lie between the profession of Arms and the mind that puts things into words. And I ask myself: why?"

Perhaps this is why so many of the classic accounts of the Great War were written some years after the Armistice. Time was needed to sift the memories and determine what the participants actually thought about what they had been through. I remember, when writing my book, sifting through the pencilled notebooks of Siegfried Sassoon in the library of the Imperial War Museum (formerly the institution known as Bedlam!) and following the twists and turns of his scribbled attempts to start the story which became the classic Memories of an Infantry Officer which did not appear until 1930. Others managed to gather their thoughts more quickly. A.P. Herbert's The Secret Battle (1919) is one of the often overlooked fictional accounts that appeared very soon after the end of the War. I strongly recommend it.

Ford considered that the practical preoccupations of being a soldier "absolutely numbed my powers of observation"but his account of the psychology of someone trying to make sense of the war is fascinating. A good starting point for thinking more seriously about the Centenary.

Wednesday, 19 March 2014

Talking about the Poetry Pamphlet

|

| A recent pamphlet from Rack Press |

Friday, 14 March 2014

Tony Benn Remembered

|

| Tony Benn At Demonstration outside the Greek Embassy, January 2013 |

Friday, 7 March 2014

Creative Writing Courses: a Health Warning

I see that Hanif Kureishi has been at it again this time rubbishing creative writing courses and giving the media the pleasure of pointing out that he is a Professor of Creative Writing himself. As if he cared.

The old Latin tag poeta nascitur non fit [the poet is born not made] which seems to say that writing cannot be taught, makes its appearance regularly, but the debate never seems to get further than the rehearsal of what was said last time so here are Ten Things You Won't Always Hear About Creative Writing Courses [from someone who teaches non-fiction creative writing].

The old Latin tag poeta nascitur non fit [the poet is born not made] which seems to say that writing cannot be taught, makes its appearance regularly, but the debate never seems to get further than the rehearsal of what was said last time so here are Ten Things You Won't Always Hear About Creative Writing Courses [from someone who teaches non-fiction creative writing].

- Creative writing can be taught in the same way that sculpture, maths, pastry-making, carpentry and indeed anything can be taught. That's what education is for. End of debate.

- Many creative writing courses are indeed a waste of time because publishing is in crisis, risk-averse, and incapable of thinking outside its crumpled cardboard box, outlets for your perfectly honed and blame-free work are few, and the chances of being published are slim. Unlike watercolour painting where you can hang your tolerably nice picture (as I do!) of some trees in the loo, an unpublished manuscript is very sad like a crumpled party frock at dawn..

- Many creative writing courses – notoriously the Guardian and Faber varieties – are a rip-off, over-priced ventures in snake-oil marketing.

- Professors of Creative Writing are chosen because they are 'names', probably already overpaid, and most of the work is done by a class of low-paid, exploited helots

- The contemporary university is motivated by only one thing, money, and creative writing courses are perceived as an easy way of relieving people of it.

- Many of the classic nostrums of the creative writing courses are rubbish. Here's John Donne, in one of the great poems of the English language, "The Anniversary", telling not showing: 'All other things to their destruction draw/Only our love hath no decay.'

- The job of a writer is to break rules not to follow them

- A regrettable consequence of the exploding creative writing industry is that writing, which is a vocation, becomes a career choice and taking one is like enrolling on a snobby MBA in the hope that you will found your own organic marmalade empire

- The most serious case against creative writing courses is that they foster uniformity and dullness; students are taught what to avoid ['too many adjectives'] which results too often – one can see it most clearly in contemporary poetry – in a kind of toothpaste poetry, slickly oozing out in a uniform and colourless trail. The stripe doesn't fool us.

- Writers can benefit from sharing work with their peers and receiving constructive criticism – I missed out on this in my early writing years and regret it – but in the end one learns to write from reading with passion and creativity and from following the promptings of one's ungovernable creative imagination.

Oh, I didn't want the professorial job anyway.

PS No mention above of the actual students on such courses, working with whom, for those of us who teach them, is what makes the whole show worthwhile.

PS No mention above of the actual students on such courses, working with whom, for those of us who teach them, is what makes the whole show worthwhile.

Monday, 17 February 2014

Biography and the Need to Know

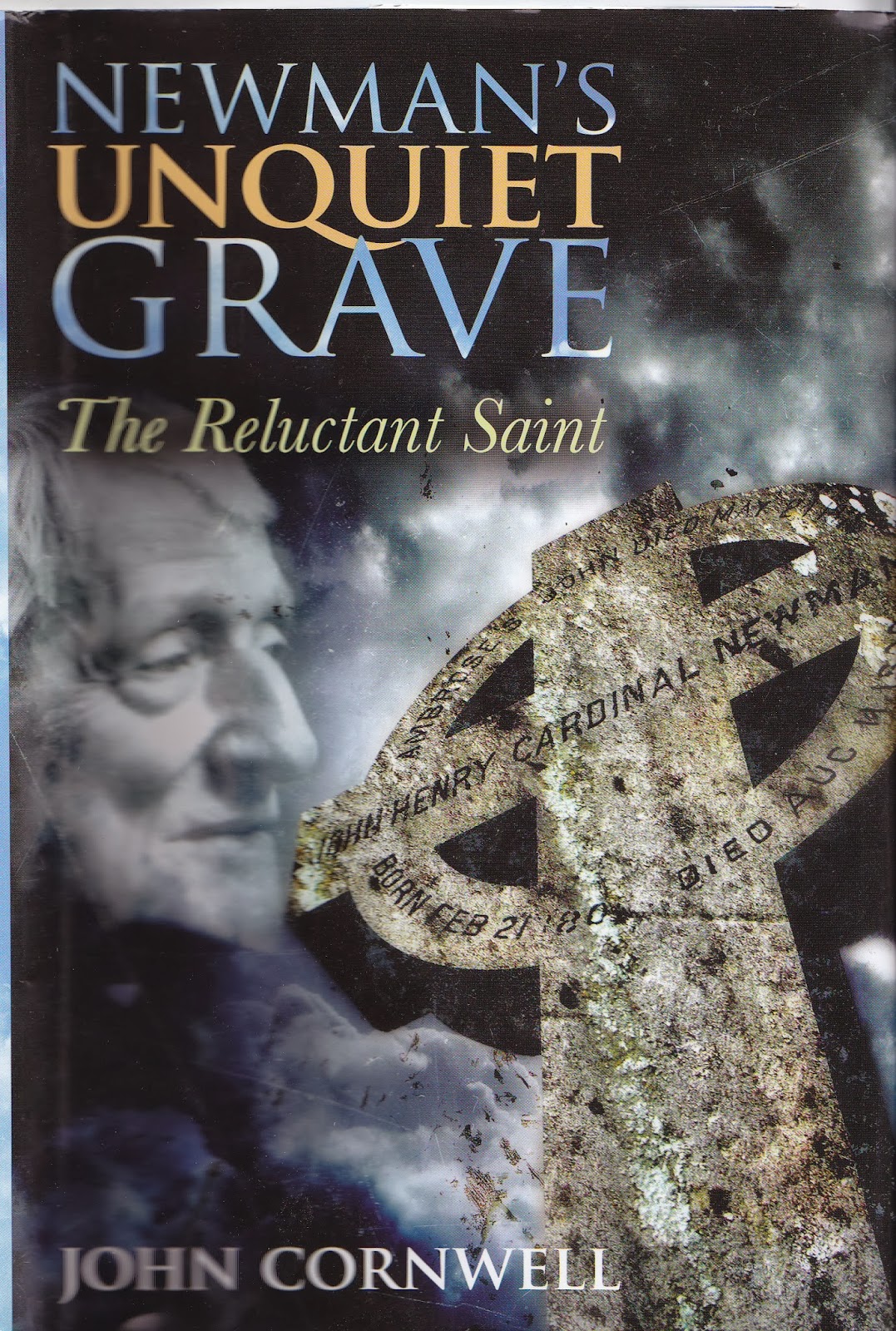

Having just read John Cornwell's biography of John Henry Newman, the Victorian theologian and prose stylist (much admired by James Joyce) I have been thinking about the ethics of biography. It used to be "scandal" of a heterosexual kind that exercised, if not biographers, then the climate of publicity around the publication of their books. Now the fun has switched to finding out whether or not the subject was homosexual. This immediately raises three questions for me: what business it it of ours? what standard of proof is required? and who cares?

When it comes to Newman (on the Catholic Church's long or shortlist for canonisation as a saint) the fact that he insisted on being buried in the same grave as his lifelong friend Ambrose St, John is enough for some, including my old friend, gay rights campaigner, Peter Tatchell. Peter may be right that Newman was gay but equally the relationship with Ambrose St John could have been a deep, affectionate same-sex friendship (Cornwell's view). The fact is that we don't know. These buttoned-up Victorians, it turns out, were very emotional people. They used the language of love to describe friendships and Cornwell shows how this was a feature also of the Romantic poets like Wordsworth and Coleridge. The world of the celibate priest is one that is closed to most of us. It is hard to imagine what it might mean and, at the end of the day, people's private sexuality, the ways they choose to come to terms with it or sublimate it, is their own. In the case of the Catholic Church, however, the terrible child sex abuse scandals committed by priests and monks mean that the question can't be left there. If celibacy doesn't work (assuming that is the reason for the scandals which, of course, also happen in the non-celibate world too) then the issue does need to be confronted. Personally, I am grateful for the delicate way that Cornwell handled this issue in his biography saying no more and no less than was warranted.

When it comes to Newman (on the Catholic Church's long or shortlist for canonisation as a saint) the fact that he insisted on being buried in the same grave as his lifelong friend Ambrose St, John is enough for some, including my old friend, gay rights campaigner, Peter Tatchell. Peter may be right that Newman was gay but equally the relationship with Ambrose St John could have been a deep, affectionate same-sex friendship (Cornwell's view). The fact is that we don't know. These buttoned-up Victorians, it turns out, were very emotional people. They used the language of love to describe friendships and Cornwell shows how this was a feature also of the Romantic poets like Wordsworth and Coleridge. The world of the celibate priest is one that is closed to most of us. It is hard to imagine what it might mean and, at the end of the day, people's private sexuality, the ways they choose to come to terms with it or sublimate it, is their own. In the case of the Catholic Church, however, the terrible child sex abuse scandals committed by priests and monks mean that the question can't be left there. If celibacy doesn't work (assuming that is the reason for the scandals which, of course, also happen in the non-celibate world too) then the issue does need to be confronted. Personally, I am grateful for the delicate way that Cornwell handled this issue in his biography saying no more and no less than was warranted.

Saturday, 18 January 2014

Remembering Bruce Chatwin

Today is the 25th anniversary of the death of Bruce Chatwin and his former school, Marlborough College, was the venue for a two-day colloquium on the writer that kicked off yesterday with a lecture from me and today lectures from Jonathan Chatwin and Susannah Clapp. It was a great pleasure to witness the students (Marlborough is now fully co-educational) showing their enthusiasm for Chatwin and reading out extracts from him so well. I ran a short travel-writing workshop with a group of sixth formers (using a passage from The Songlines to spark discussion) and it is clear that his influence is still strong. His old friend Michael Cannon unveiled a memorial plaque to him and there was much discussion about how seriously to take claims that he had not enjoyed his schooldays. As someone pointed out, in the 1950s no one expected to enjoy their boarding school experience but today's Marlburians certainly seem to be very happy and lively. And I have my commemorative mug!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)