"A precondition for reading good books is not reading bad ones: for life is short" - Schopenhauer.

Thursday, 23 December 2010

Telling the Truth Must Stop!

Prepare for shock revelations on Christmas Eve that snow on one's boots melts when they are put in front of the fire.

Joyeux Nöel, comrades.

Wednesday, 22 December 2010

No Books of the Year?

Meanwhile I am about to disappear into the snowy hills of Wales. So adieu and Season's Greetings to one and all.

Wednesday, 8 December 2010

Real Bloomsbury

This week sees the publication of my latest book, Real Bloomsbury, from Seren Books. It's the newest in a series edited by Peter Finch that began in Wales with his pioneering Real Cardiff and the idea is that writers respond to a place in a very personal or offbeat way. It was great fun to research and write and I hope you will enjoy it. The Bloomsbury Group (Virginia et al.) obviously figure though I try to stop them hogging the stage and there's plenty of other interest, associations, present day diversions to fill a book even without them.

This week sees the publication of my latest book, Real Bloomsbury, from Seren Books. It's the newest in a series edited by Peter Finch that began in Wales with his pioneering Real Cardiff and the idea is that writers respond to a place in a very personal or offbeat way. It was great fun to research and write and I hope you will enjoy it. The Bloomsbury Group (Virginia et al.) obviously figure though I try to stop them hogging the stage and there's plenty of other interest, associations, present day diversions to fill a book even without them.

Monday, 29 November 2010

Andrew Marvell: Can I See Your Pass?

Thursday, 18 November 2010

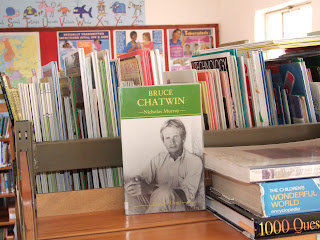

Chatwin Under the Sun

It is possible to quote some rather absurd passages, but usually Elizabeth has got there first with a wryly deflating footnote. And there are some unexpected moments, such as his discomfort at emerging as "a writer" in the 1980s, a role, relished by his friend Salman Rushdie, but one that he hated. He didn't want to be lionised, televised, invited to review books and so forth. He just wanted to disappear and write his next book. There are contradictions of course. He was televised. He did court the rich and famous and his friends always seemed to have been utterly exceptional in his estimation, the dull and the pedestrian members of the population never seemingly coming to his attention. But one day he had a group of writers around to lunch at his Oxfordshire home and found their noisy, shrill posturing unbearable: "a lot of egos sounding off, but we were able to open the windows so all the talk blew out over the sheep..."

And I can forgive him everything for writing: "With so many 'cooked-up' books knocking around, I don't really believe in writing unless one has to."

Monday, 8 November 2010

Houellebecq: I Was Wrong

Echenoz Completes His Trilogy

Echenoz is drawn to these solitary, strange, obsessive characters in what his publishers call "fiction sans scrupules biographiques" and he recounts the story of Tesla, here called Gregor, with economy, dry wit, and a nice sense of period flavour (early 20th century New York). Exquisite.

Tuesday, 26 October 2010

Houellebecq Strikes Again

Any day now they will be announcing the results of the Prix Goncourt, whose recent prize winners, I have to say, have been more interesting to me than the Man Booker's in the UK. One title being tipped is enfant [well he's actually 53] terrible Michel Houellebecq's new novel La carte et le territoire. The low argument (and literary prizes of this kind are usually about low arguments) is that it will win because (a) it is long overdue (b) it's crazy that one of the most read French novelists worldwide hasn't won it and (c) under Buggins' turn it's Flammarion's turn, that being the way French literary prizes work, and MH is their big one this season. The argument against is that (a) Houellebecq is far too politically incorrect (b) he has upset too many people and (c) the Ben Jelloun Question. The last of these is the only one that matters. In his regular column in an Italian newspaper, the French North African novelist Tahar Ben Jelloun (whom I admire far more than Houellebecq) laid into MH's latest novel saying he had wasted three days of his life reading it and that its trick of inserting real people into the narrative simply revealed a lack of inventive power. Ben Jelloun matters because he is on the Goncourt jury.

Any day now they will be announcing the results of the Prix Goncourt, whose recent prize winners, I have to say, have been more interesting to me than the Man Booker's in the UK. One title being tipped is enfant [well he's actually 53] terrible Michel Houellebecq's new novel La carte et le territoire. The low argument (and literary prizes of this kind are usually about low arguments) is that it will win because (a) it is long overdue (b) it's crazy that one of the most read French novelists worldwide hasn't won it and (c) under Buggins' turn it's Flammarion's turn, that being the way French literary prizes work, and MH is their big one this season. The argument against is that (a) Houellebecq is far too politically incorrect (b) he has upset too many people and (c) the Ben Jelloun Question. The last of these is the only one that matters. In his regular column in an Italian newspaper, the French North African novelist Tahar Ben Jelloun (whom I admire far more than Houellebecq) laid into MH's latest novel saying he had wasted three days of his life reading it and that its trick of inserting real people into the narrative simply revealed a lack of inventive power. Ben Jelloun matters because he is on the Goncourt jury. So what about the novel itself? I found it better written than his previous novels, both at the level of its prose, and in its tighter construction. Some have found it less obviously provocative and, even more surprisingly, it is almost equable in parts. There is also almost no sex in it which is a turn up for the books. I think these critics who imply that the fire has gone out of him are wrong and that the old provocations are there even if they are a little less in-your-face. The MH we love, mordant, savagely deadpan in his satirical swipes is very much in evidence and I found it very funny for that reason. Yes, he inserts himself in the narrative but not in some sort of arch metafictional manner. He does it to send himself up as a smelly, unwashed slob living in a hideous bungalow in Ireland feeding himself on cheap charcuterie, swilling cheap south American wine, and being generally surly and unattractive. It's an old joke but it works. The book sends up the contemporary art market through its central character Jed Martin, an artist with a touch of the master about him, and also aims at a range of Houellebecquian targets like assisted suicide, cremation, "inherently fascist" airlines etc etc. It is also about ageing and death and his usual big subjects and it is about NOW. He loves to describe, with toxic accuracy, the mediocrity of so much in the contemporary world. Much of his "provocation" resides in his inability to praise what we know shouldn't be praised but regularly is. Unfortunately I can't tell you what happens in the final third section of the novel because it will spoil your enjoyment but it is brilliantly done and funny. It also made me think that he could have a future as the author of romans policiers. But it probably won't win the Prix Goncourt.

Tuesday, 19 October 2010

Twenty Thousand Stars In the Sky

Wednesday, 13 October 2010

What is a Best Selling Author?

Friday, 8 October 2010

Kadare and Kafka: an Update

Bloomberg's HQ in Finsbury Square is a marvel. Through its stage-lit spaces, where copious security people stand every few yards like flunkeys at a Versailles court ball, and where in the refreshment area everything is free, including great domed piles of bananas, cookies, apples and cherry tomatoes, and large screens everywhere broadcast the latest share prices and financial news (and the breaking news that Mario Vargas Llosa had just been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature) the bemused Kadare, his interpreter and his interviewer moved as if through the film set for a remake of Brave New World. But Bloomberg are generous hosts and it was good to learn that The Accident is being discussed at their next in-house book group.

Monday, 4 October 2010

The Other Hay-on-Wye

Friday, 24 September 2010

Polyglot Music: Joseph Roth and the Imbecility of Patriotism

One might say: Patriotism has killed Europe...European culture is much older than the European nation states. Greece, Rome, Israel, Christendom and Renaissance, the French Revolution and Germany's eighteenth century, the polyglot music of Austria and the poetry of the Slavs: these are the forces that have formed Europe...All are naturally opposed to the barbarity of so-called national pride.

The imbecile love of the "soil" kills the love of the earth. The pride of being born in a particular country, within a particular nation, wrecks the feeling of European universality."

Joseph Roth, "Europe is Possible Only Without the Third Reich" (1934) from The White Cities

Tuesday, 14 September 2010

Borges and the Toothbrush or What to Read on Holiday

Monday, 13 September 2010

The Hell of Forgotten Books

Tuesday, 7 September 2010

Josipovici and the Story of Modernism

Tuesday, 17 August 2010

La rentrée littéraire

Recently, the critic and novelist Gabriel Josipovici, was reported as having said that contemporary British writers weren't up to much though, as he explained last week in a letter to the TLS, the reporting of his comments, buried in a serious work of criticism forthcoming from Yale UP, trivialised them. He bravely refused to be dragged on to Newsnight to take part in a shallow staged debate about the merits or otherwise of Amis, Rushdie, McEwan et al. His apparent argument that, in the wake of the great moderns, contemporary writing in Britain doesn't measure up, misses some vital dimension, sounds interesting and highly plausible. So what of the comparable position in France? Will we be told? I doubt it.

Tuesday, 10 August 2010

Tony Judt and Reminiscence

Tuesday, 3 August 2010

Josipovici And Other Animals

Josipovici, in spite of having written an affecting memoir claims that he is suspicious of the genre. He quotes his mother's view: "...to write one's memoirs is to cease to look forward. It's a form of nostalgia and self-indulgence." He says much later in the book that autobiography is unsatisfactory because: "A person can never grasp the trajectory of their own life, not only because that trajectory is not over till their life ends, but because a life is more than what one can say, it is more than one can think.. It can only be lived, not told – not told by the liver, that is, but only by another." That is why he chose to write another person's life. Again, he says: "A memoir would have left me to wallow in my sorrow; writing the life of another, of that other, was what I needed to do, and I now see why." We can only be grateful that he overcame his reservations and wrote this book.

Thursday, 29 July 2010

Saturday, 24 July 2010

Kafka Again

Tuesday, 20 July 2010

Bruce Chatwin by Bike and Who Owns Kafka?

[You can now see this in BBC iplayer for a limited period. Click here

Yesterday I had a call from the BBC World Service to appear live on their early evening news programme to be interviewed about the controversy surrounding the Kafka archive. Ten boxes of material formerly owned by Esther Hoffe, secretary to Kafka's friend, Max Brod, who left them to her and who famously defied Kafka's request that all his unpublished writings be destroyed, are being currently fought over. Hoffe's two daughters are engaged in legal battles to stop the boxes being opened but no one knows what they contain. Yesterday one of the boxes, in a bank vault in Zurich, was being examined by a scholar under the instruction of the court so we may still not know for some time what is on the inventory. On the programme I suggested that it is unlikely that they will contain any major unpublished work, since Brod dedicated himself to promoting and massaging Kafka's reputation and would surely not have missed a chance to publish more of it. Probably, they will contain Brod's own diaries and letters, though "drawings" have been mentioned in the press. There is bound to be much of interest but we will have to wait. Meanwhile both the Jewish National Library in Israel and the German Literary Archives in Marbach are fighting to acquire the eventual material. As I suggested on the programme, Kafka's body is spread out on a table, all four limbs being tugged in different directions: born in Prague in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1883 and thus an Austrian, waking up in 1918 to find himself a citizen of the Czech Republic, a Jew, and a master of modern German prose. According to the Israelis his archive belongs as of right to them, but the Germans surely have an equal right since language is always the defining issue when considering a writer, and what about the Czechs?

We will have to be patient.

Tuesday, 13 July 2010

Craig Raine and The Critics

It is a basic rule of this blog that I only talk about books I have read and so I can't say anything about Craig Raine's new novel, Heartbreak, because I haven't yet read it. Like everyone else, however, I have read Terry Eagleton's hatchet-job in the London Review of Books, and it has reminded me – to compare great with small – of my own 2001 novel, A Short Book About Love which also provoked the comment that it was "not really a novel". Raine is not shy of controversy of course and can look after himself. I have to declare an interest in that his magazine Areté published two pieces by me (one very long, one very short) and in consequence I was invited to his lovely house in Oxford for the 10th birthday bash of the magazine where many famous literati pullulated. Since both pieces were published not as a result of any currying of favour with this charmed literary élite whom we all love to hate (I didn't know any of them so there were no strings to pull) but by the simpler expedient of putting them in an envelope addressed "Dear Sir" I salute his openness to unsolicited material, always the mark of a good editor. As former poetry editor of Faber and Faber and putative founder of the Martian school of poetry, and chum of Martin, Ian, Julian etc, Raine was bound to attract enemies but I can only say he was very nice to me.

The new book, which appears to be a series of episodic reflections and digressions on the subject of love (a fair description also of my book) raises the question of what is and is not a novel. The epigraph to my book was taken from Dr Johnson, who defined the novel in his A Dictionary of the English Language as "A small tale, generally of love." My definition would be "whatever you want it to be". Aldous Huxley said there are no rules governing the novel except that it must be interesting and I agree. What we want writers to be is inventive, original, entertaining. If they don't have plots – or beginnings, middles, and ends – then so be it, as long as they are a pleasure to read. In my last post about Isaac Bashevis Singer I said how much power there still is in realist fiction and I believe this. But there is also scope for the sort of writing that takes liberties and gives pleasure in the process. So let people break the rules and let the puritans be discomfited.

Now I will go and read Raine's book...

Friday, 2 July 2010

Isaac Bashevis Singer and the Vitamin Pills

Wednesday, 16 June 2010

How Was Your Bloomsday?

The sun is shining, the longest day is still to come, and I have a feeling that a re-reading of Ulysses is on the way. My lovely green Bodley Head 1960 edition [I don't give a fig about the 'Joyce Wars' of the scholars over which text is to be preferred] is on the shelf, waiting to be taken down: "Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed..."

Definitely.

Tuesday, 15 June 2010

Life-Writing: The Arvon Book

Anyone in London interested in this subject might like to know that I am teaching a 12-week course on it at The City Lit this autumn.

Sunday, 16 May 2010

The British Library: Work for Free!!!

"writing for our staff intranet and newsletter; creating intranet pages; monitoring the team’s day-to-day work; updating notice boards and generally helping out with the administration in our department. We’re looking for someone with great communication and interpersonal skills...An interest in marketing communications and/or public relations, an excellent standard of written English and the ability to use a PC and the internet would be of advantage."

There's just one catch: you don't get paid. This is of course a job for an unpaid skivvy, aka "intern". Once upon a time young graduates (for that is my guess as to whom the likely appointee will be) got real work experience by doing a real job (in fact this one sounds a bit like my first media job) but now a public body like the British Library (Chief Executive's salary £195,000) is cynically hoping to get work done by not paying someone at all. Did the staff unions agree to this? Where will the employee live? How will they pay the rent? How will they eat?

It could be worse because there are reports that in the US, graduates actually pay in some cases for the privilege of being a work-donor. But is this going to be the pattern now in the British public sector?

But I agree, "fairness" is a good thing. I can't get enough of it myself.

Monday, 3 May 2010

Gillian Tindall: A Microhistorian in Paris

Wednesday, 28 April 2010

Who Will Give a Fig for Figes?

This reminds me of a review (not anonymous) that appeared on Amazon in 1999 when my life of Andrew Marvell was published. It wasn't vindictive, just vaguely sneering, and contrasted with the very pleasing reviews the book received generally. Since no other Amazon review ever appeared this slab of disparagement has stood on the site for eleven years to confront anyone thinking of buying the book and will, no doubt, remain there across the "deserts of vast eternity". At the time, I entered the name of the self-appointed reviewer into a search box and up popped a long, laudatory review of his own book – written by himself. Now why didn't I think of that?

My fault in this instance was to have written a book about a 17th Century poet without seeking permission from the relevant academic 17th Cent. Lit. trade guilds and annoying an ambitious would-be media don on the rise by writing the book he wanted to be commissioned to write. I am always amused by academics who sneer haughtily at the general Grub Street author then go running as fast as their little legs will carry them into the nearest TV studio or literary festival tent if there is the slightest chance of being on the telly.

Monday, 19 April 2010

We're the Tops – Well, Near the Bottom, Actually

Some years ago I read an article suggesting that there were so many literary prizes and awards that you had to try pretty hard to avoid securing one. Having never won a literary prize (though I was once on a shortlist of six for the Marsh Biography Prize alongside weighty literati like Roy Hattersley) I assure you that it is easier than people claim to avoid winning anything. So let's throw our hats in the air to Wikio (whomsoever they be) for this unexpected garland.

It makes me feel I should be blogging more regularly. I have, like many literary bloggers, been flagging a bit recently so let this be a wake-up call.

A Postscript on Literary Elections

I am currently reading V.S. Naipaul's 1958 novel The Suffrage of Elvira and it is a wonderfully witty story about an election in Trinidad circa 1950. Much more fun than page after page in the Sunday papers dribbling on about whether X looked better on TV than Y. Having not long ago read his first novel, The Mystic Masseur (1957) I have become a great fan of Naipaul's early work.

Wednesday, 14 April 2010

Literature and the Election

I am not 'cynical about politics' or trying to dodge my civic duty. I shall 'exercise my vote'. But the spectacle of the issues that matter being daily evaded by all sides does not help the digestion.

Thursday, 8 April 2010

Summer is y-comen in

Tuesday, 30 March 2010

The Luxury of Art

But one of the Guardian letter writers, Iain Morgan, Professor of Molecular Oncology at the University of Glasgow, insists that science is necessary, not to further knowledge, but because "without science and technology our country will lag behind others". Moreover – and this is his killer conclusion – "only by science and technology generating inventions and wealth can we afford the luxury of art". Why do I find this such a miserable conclusion?

Because art is not "a luxury", a by-product of wealth-creation. Art simply exists, it is. Art is fundamental, necessary, needs no justification, is the element in which sentient, intelligent human beings move like fish in a stream. It is not a by-product or an incidental consequence of anything. Given the current state of British universities where money-making is the summum bonum, I suppose it is not surprising that such ideas as that of the Prof. flourish.

Friday, 12 March 2010

The Literature Sector: Production Values

The following appears in the latest newsletter of the Welsh Academi. Comment, I think, is superfluous:

"Creative & Cultural Skills is inviting the literature sector to contribute to a new plan to develop the skills needs of the industry. The Literature Blueprint will be a workforce development plan for literature in the UK. It will analyse the skills needs of the literature sector and propose key actions in response.

The plan is focused on creative writers and those who support them. They would like to hear a range of views from the sector, from writers across different disciplines to writers’ networks and anyone who works to support the development of the literature sector. The plan will be UK-wide.

Tom Bewick, Group Chief Executive, Creative & Cultural Skills, said: “The UK is rightly proud of its literature sector, which encompasses a range of working practices and business models. To ensure the continued success of the sector in a time of intense technological and economic change, we need to focus now on developing those skills that will be needed in the future.”

Antonia Byatt, Director, Literature Strategy at Arts Council England, said: “We are delighted to have been partners with Creative & Cultural Skills in developing the Literature Blueprint. To ensure that everybody can access high-quality literature experiences, both now and in the future, is at the heart of our work, and the development of skills is vital in this aim.”

Wednesday, 10 March 2010

Paweł Huelle: Mercedes-Benz

Wednesday, 24 February 2010

Amazing Amazon: Part Two

Tuesday, 23 February 2010

Amazon The Corporate Behemoth

Grrrr!

Tuesday, 9 February 2010

Gazmend Kapllani and Border Syndrome

This short book is written in thirty sections which combine the stories of a group of those Albanians who, after the fall of the Communist regime, poured over the border with Greece, as Kapllani himself did in 1991, with reflections on what he calls "border syndrome" which is "an illness that's difficult to describe with precision". There are vivid moments, like the first visit of the Albanians from a brutal and Spartan political regime to a supermarket in northern Greece, and overall the book offers an insight into the condition of the migrant in a week when British newspapers reported the deaths from hypothermia of some European migrants living in tents in the British countryside. We tend to think that exploitation and hardship of a kind meted out to migrants in our midst happens elsewhere, not in the farms that supply our cheap supermarket fruit and vegetables, making us complicit in that suffering. Fortunately, migrants of this kind conveniently stay out of sight so that we don't have to think about them and our responsibility for what they go through.

Thursday, 4 February 2010

Clough and The Blue Plaque Business

To North London yesterday for the unveiling of a plaque to the poet Arthur Hugh Clough (1819-1861) at the house in St Mark's Crescent, NW1 where Clough lived from 1854 to 1859. According to Clough scholar, Sir Anthony Kenny, pictured here, the poet didn't, er, actually write anything while he was here, but anything that raises the profile of this excellent and astonishingly modern-sounding Victorian poet must be a good thing. Talking afterwards to someone from English Heritage, the body that masterminds the plaque-business, I thought I sensed some scepticism about Clough's status, not so much in the canon of English poetry (the poet Christopher Reid who was there agreed with me that he is one of the best half dozen English poets of his period – which seemed to astonish the heritage people) as in the canon of The Higher Celebrity. When I suggested en passant that there should be a plaque to William Empson, author of that classic of 20th century literary criticism, Seven Types of Ambiguity, on the house at 65 Marchmont Street, Bloomsbury where the book was written in 1929-30 I was the recipient of one of those oh-God-here's-one-of-those-loony-obsessives looks. I can see that it's hard for the adjudicators to judge who is deserving of this kind of honour but I had that feeling I often get in these situations of sudden gloom induced by the mournful tolling of the great lugubrious bell of English cultural populism. Just like being in a publisher's office and suggesting a life of Arthur Hugh Clough, for example, when embarrassed faces turn to the window and someone suddenly finds there is a phone to answer. In a culture of lists and rankings and "no one reads people like X" how can the heritage industry buck the trend of sticking with what's safe and consensual?

To North London yesterday for the unveiling of a plaque to the poet Arthur Hugh Clough (1819-1861) at the house in St Mark's Crescent, NW1 where Clough lived from 1854 to 1859. According to Clough scholar, Sir Anthony Kenny, pictured here, the poet didn't, er, actually write anything while he was here, but anything that raises the profile of this excellent and astonishingly modern-sounding Victorian poet must be a good thing. Talking afterwards to someone from English Heritage, the body that masterminds the plaque-business, I thought I sensed some scepticism about Clough's status, not so much in the canon of English poetry (the poet Christopher Reid who was there agreed with me that he is one of the best half dozen English poets of his period – which seemed to astonish the heritage people) as in the canon of The Higher Celebrity. When I suggested en passant that there should be a plaque to William Empson, author of that classic of 20th century literary criticism, Seven Types of Ambiguity, on the house at 65 Marchmont Street, Bloomsbury where the book was written in 1929-30 I was the recipient of one of those oh-God-here's-one-of-those-loony-obsessives looks. I can see that it's hard for the adjudicators to judge who is deserving of this kind of honour but I had that feeling I often get in these situations of sudden gloom induced by the mournful tolling of the great lugubrious bell of English cultural populism. Just like being in a publisher's office and suggesting a life of Arthur Hugh Clough, for example, when embarrassed faces turn to the window and someone suddenly finds there is a phone to answer. In a culture of lists and rankings and "no one reads people like X" how can the heritage industry buck the trend of sticking with what's safe and consensual?

Thursday, 28 January 2010

Amis Strikes Again

Does Martin Amis have no friends who can have a quiet word with him? No sooner has he finished rubbishing that increasingly large and influential section of society, the elderly, who, he recently informed us "stink" (subtlety always his hallmark) than he turns his attention to his fellow writers. Prospect magazine in a preview of an interview it is about to publish with the Great Writer offers us a view of the second rate talents against whose mediocrity the talent of Amis shines out more brightly: "Coetzee, for instance—his whole style is predicated on transmitting absolutely no pleasure,” he explained. “I read one and I thought, he’s got no talent. But the denial of the pleasure principle has got a lot of followers.” How did we get here – to a world where Coetzee is declared to have no talent and Amis is fêted? Answers on a postcard please.

Wednesday, 27 January 2010

A Poet Wins!

Wednesday, 13 January 2010

Poetry Readings Are Cool OK?

One of my Christmas gifts this year was J. G Ballard's absorbing autobiography, Miracles of Life, which at one point presents his observations on poetry readings: "Most poets were products of English Literature schools, and showed it; poetry readings were a special form of social deprivation. In some rather dingy hall a sad little cult would listen to their cut-price shaman speaking in voices, feel their emotions vaguely stirred and drift away to a darkened tube station."

Thursday, 7 January 2010

Snowfall

I don't mean to be rude but when mid-Wales was covered in snow last week it somehow didn't seem to be as grave as when it actually fell in London – giving Gandhi in Tavistock Square, semi-naked on his plinth, a tonsure of white overnight. London and the south-east still think of themselves as the centre of the universe and until something occurs inside the M25 it's not judged a real event at all.

I don't mean to be rude but when mid-Wales was covered in snow last week it somehow didn't seem to be as grave as when it actually fell in London – giving Gandhi in Tavistock Square, semi-naked on his plinth, a tonsure of white overnight. London and the south-east still think of themselves as the centre of the universe and until something occurs inside the M25 it's not judged a real event at all.