Does it matter what one writes with? Creative writing tutors have their endearing prohibitions and recommendations (write about what you know, don’t use adjectives etc etc) but the physical medium of writing itself tends to be dismissed as nothing more than an irrelevant personal quirk that has little bearing on what gets written.

But does it? Iris Murdoch famously preferred to write in fountain pen (“One should love one’s handwriting”) and the mystic union of hand and writing instrument (quill or MacBook) should not, perhaps, be too quickly dismissed. In a similar way, on a writer’s desk a pebble from a Greek beach, a statuette, a piece of coloured glass, can be the crucial co-ordinates of creativity, aids to the chancy manoeuvres of composition.

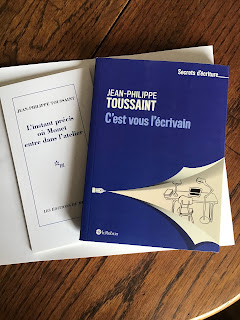

A new book from the French writer Jean-Philippe Toussaint, C’est vous l’écrivain (You are the Writer) takes it title from a remark offered to Toussaint when his first novel was accepted by the legendary Jerome Lindon of Éditions de Minuit, publisher of the nouveau roman of the 1950s. The fledgling author timorously offered Lindon a list of post-acceptance alterations and second-thoughts, fearing that this would be taken wrongly but Lindon coolly replied: “c’est vous l’écrivain,” with the unspoken warning, however, that the writer might propose but, as fearsome editor, obsessed with detail, Lindon’s scalpel would not stay long in its sheath.

Toussaint describes in fascinating detail his own writing methods, the succession of Apple computers he has worked on, each page printed off for intense reworking with a hand-held pen, fonts played with, patterns of text laid out on the page for evaluation (he prints a bizarre example of cramped micro-paragraphs arranged like troops at a dictator’s victory parade), dictionaries ransacked, everything subjected to forensic re-writing. Not for him the astonishingly rapid productivity of Stendhal who could hardly have had time to check for a missed comma (The Charterhouse of Parma’s 500 pages tossed off in 53 days).

Ford Madox Ford, in his characteristically digressive memoir/fiction It Was the Nightingale (1934) confessed that he disliked writing with a pen, in part because of arthritic pain. He was forced to use a new Corona typewriter and even tried dictation to a stenographer – but this made it all too easy: “If I have to go to a table and face pretty considerable pain I wait until I have something worth saying to say it in the fewest possible words.” Ford had put his finger on a crucial need for any writer: to have an invisible antagonist to wrestle with. If it isn’t the product of sweat and toil it has come too easily. Unlike the computer which has made rewriting and re-positioning text so effortless, Ford found insupportable the typewriter’s requirement for him to redo a whole page in order to eliminate a mistake (“I detest a typewriter page showing any corrections”). He went to extraordinary lengths to avoid having to retype, even finding a new context in the words around it for the mistaken word in such a way that it now worked without alteration. But he knew the ultimate truth: “Elimination is always good.”

In the end Ford Madox Ford resolved to return to writing with a pen. His advice to any writer was “in composing make your circumstances as difficult as possible” but erase any mistakes with “bold, remorseless black strokes”.

For Jean-Philippe Toussaint, who began with an Apple LC2 in 1993, and has passed through every ordinateur portable from that stable since then, these years have seen “a silent revolution” in the processing of words which he judges nonetheless as “a natural evolution of the practice of writing” leaving him, however, to speculate about what communications revolution is waiting for his old age.

For my own part, I am grateful that I never learned to touch type, my two-fingered dexterity being quite fast enough, if not quite Stendhalian. As I watch the fingers of others flick like lightning over the keyboard I am relieved that I cannot go any faster. I know that slowness is good for me, hauling me back from the precipice of a too-fluid sentence. As Ovid urged, in another context, lente, lente, currite noctis equi.

But strictures about writing will always retain a certain specious logic. What looks like a rule, a necessity, a universal truth, will turn out to be merely a piece of advice that might work for you but not necessarily for me. Closer to a lucky charm than a law of physics, these strictures aid us in the good work of being hindered, help to convince us that we are on the stony but right track.

The only immutable law, however, remains the one that should be carved into the marble lintel of every writing school: all writing is re-writing.