It sometimes seems as though 2009 has been the year of Lists. Endless lists, with The Guardian and The Observer particularly obsessed with this form of rather childish journalism. Instead of articles of intellectual discovery or exploration we get endless drilling into rows of the usual suspects, the same old names, the same old cultural 'celebrities', the safe choices. And we stop caring. It has been made worse by the fact that this year's lists can play the end-of-the-decade variation as the "noughties" vanish unlamented. Can it really be a decade since I was on the streets of a little market town in the Welsh Marches at midnight celebrating the end of the 20th Century? And what are centuries anyway? – 500 years ago this pew end in my picture (I seem to be right out of robins) was carved in Geneva cathedral and it's still there, looking well on it.

It sometimes seems as though 2009 has been the year of Lists. Endless lists, with The Guardian and The Observer particularly obsessed with this form of rather childish journalism. Instead of articles of intellectual discovery or exploration we get endless drilling into rows of the usual suspects, the same old names, the same old cultural 'celebrities', the safe choices. And we stop caring. It has been made worse by the fact that this year's lists can play the end-of-the-decade variation as the "noughties" vanish unlamented. Can it really be a decade since I was on the streets of a little market town in the Welsh Marches at midnight celebrating the end of the 20th Century? And what are centuries anyway? – 500 years ago this pew end in my picture (I seem to be right out of robins) was carved in Geneva cathedral and it's still there, looking well on it."A precondition for reading good books is not reading bad ones: for life is short" - Schopenhauer.

Wednesday, 23 December 2009

A New Year Resolution

It sometimes seems as though 2009 has been the year of Lists. Endless lists, with The Guardian and The Observer particularly obsessed with this form of rather childish journalism. Instead of articles of intellectual discovery or exploration we get endless drilling into rows of the usual suspects, the same old names, the same old cultural 'celebrities', the safe choices. And we stop caring. It has been made worse by the fact that this year's lists can play the end-of-the-decade variation as the "noughties" vanish unlamented. Can it really be a decade since I was on the streets of a little market town in the Welsh Marches at midnight celebrating the end of the 20th Century? And what are centuries anyway? – 500 years ago this pew end in my picture (I seem to be right out of robins) was carved in Geneva cathedral and it's still there, looking well on it.

It sometimes seems as though 2009 has been the year of Lists. Endless lists, with The Guardian and The Observer particularly obsessed with this form of rather childish journalism. Instead of articles of intellectual discovery or exploration we get endless drilling into rows of the usual suspects, the same old names, the same old cultural 'celebrities', the safe choices. And we stop caring. It has been made worse by the fact that this year's lists can play the end-of-the-decade variation as the "noughties" vanish unlamented. Can it really be a decade since I was on the streets of a little market town in the Welsh Marches at midnight celebrating the end of the 20th Century? And what are centuries anyway? – 500 years ago this pew end in my picture (I seem to be right out of robins) was carved in Geneva cathedral and it's still there, looking well on it.Monday, 14 December 2009

James Hanley: The Closed Harbour

The writer James Hanley (who always pretended he had been born in Dublin in 1901 but who was actually born in Liverpool in 1897) is one of those (all too numerous!) interesting authors who achieve a great deal of respect from their peers and a discerning readership but who never quite succeed in breaking through to a wider public. I wrote about him in my book on Liverpool and its writers So Spirited A Town: Visions and Versions of Liverpool (2008). The latest of his novels to be reprinted is The Closed Harbour (1952) set in Marseilles not long after the war and centring on a sea captain, Eugène Marius, who is desperately seeking work from the city's shipping offices but whose career has been blighted by a seeming error of judgement (shades of Conrad's Lord Jim) involving the death of a relative at sea under his command. It is a characteristic Hanley study of a haunted individual battling against the odds and the grimness he relishes is augmented by an effective portrait of an unforgiving and vengeful mother who arrives in Marseilles to rub salt in the old salt's wounds. This is not, you will have gathered, a light and entertaining read but as an unflinchingly realistic portrait of a man struggling (and failing) to defeat his demons it has undeniable power. With news that the "Faber Finds" series is about to re-issue some of his earlier work might a Hanley revival, always promised but never delivered, be on the way?

The writer James Hanley (who always pretended he had been born in Dublin in 1901 but who was actually born in Liverpool in 1897) is one of those (all too numerous!) interesting authors who achieve a great deal of respect from their peers and a discerning readership but who never quite succeed in breaking through to a wider public. I wrote about him in my book on Liverpool and its writers So Spirited A Town: Visions and Versions of Liverpool (2008). The latest of his novels to be reprinted is The Closed Harbour (1952) set in Marseilles not long after the war and centring on a sea captain, Eugène Marius, who is desperately seeking work from the city's shipping offices but whose career has been blighted by a seeming error of judgement (shades of Conrad's Lord Jim) involving the death of a relative at sea under his command. It is a characteristic Hanley study of a haunted individual battling against the odds and the grimness he relishes is augmented by an effective portrait of an unforgiving and vengeful mother who arrives in Marseilles to rub salt in the old salt's wounds. This is not, you will have gathered, a light and entertaining read but as an unflinchingly realistic portrait of a man struggling (and failing) to defeat his demons it has undeniable power. With news that the "Faber Finds" series is about to re-issue some of his earlier work might a Hanley revival, always promised but never delivered, be on the way?Saturday, 28 November 2009

Laugh? I Nearly Cried.

Geneva, where I have spent the past week (don't ask) is a peaceful sort of place, I thought, until I got a whiff of teargas earlier. The city is so neat and tidy and full of solid bourgeois moneyed Calvinist respectability that even the yobs and hoodies look positively unthreatening but today there seem to have been at least three manifestations: one was a string of tractors chugging through the city centre (farmers doing what they do so well, asking for more); people protesting against people protesting against mosque-building ("a third Crusade?" asked one poster on a neat set of boards provided by the municipality – we don't do flyposting in this town); and a march against the arms trade. I think it was the latter that brought out the heavy police in crash helmets and visors and tear-gas guns at tea time. I was waiting for a bus outside the central station when they started firing tear gas canisters at the demonstrators, without bothering to warn the public. Imagine British riot police (not exactly covered in glory) exploding tear-gas canisters on the concourse at Paddington without bothering to tell anyone. It's horrible stuff, stinging one's cheeks, making one's eyes red, naturally, and bringing on the swine-flu-style coughs. And my crime was waiting to catch a flipping bus to Ferney-Voltaire where the great man of the Enlightenment stands on at least two pedestals in the town. Moi, I'm flying back tomorrow!

Geneva, where I have spent the past week (don't ask) is a peaceful sort of place, I thought, until I got a whiff of teargas earlier. The city is so neat and tidy and full of solid bourgeois moneyed Calvinist respectability that even the yobs and hoodies look positively unthreatening but today there seem to have been at least three manifestations: one was a string of tractors chugging through the city centre (farmers doing what they do so well, asking for more); people protesting against people protesting against mosque-building ("a third Crusade?" asked one poster on a neat set of boards provided by the municipality – we don't do flyposting in this town); and a march against the arms trade. I think it was the latter that brought out the heavy police in crash helmets and visors and tear-gas guns at tea time. I was waiting for a bus outside the central station when they started firing tear gas canisters at the demonstrators, without bothering to warn the public. Imagine British riot police (not exactly covered in glory) exploding tear-gas canisters on the concourse at Paddington without bothering to tell anyone. It's horrible stuff, stinging one's cheeks, making one's eyes red, naturally, and bringing on the swine-flu-style coughs. And my crime was waiting to catch a flipping bus to Ferney-Voltaire where the great man of the Enlightenment stands on at least two pedestals in the town. Moi, I'm flying back tomorrow!

Tuesday, 17 November 2009

Bartók: 'Not for the Faint-Hearted'

Bartók's "Duke Bluebeard's Castle" currently being staged by the English National Opera at The Coliseum and paired in a double bill with Stravinsky's "Rite of Spring" – that score still breathtaking after all these years – is a powerful work, dramatically and musically, and everyone acquits themselves well has been the general opinion.

Bartók's "Duke Bluebeard's Castle" currently being staged by the English National Opera at The Coliseum and paired in a double bill with Stravinsky's "Rite of Spring" – that score still breathtaking after all these years – is a powerful work, dramatically and musically, and everyone acquits themselves well has been the general opinion.Wednesday, 28 October 2009

Georges Perec: Still Crazy After All Those Years

The media obsession with cultural anniversaries is not always complete – look how the books pages missed the fact that this year, nearly over, has been the centenary of Malcolm Lowry – but here's one you definitely haven't thought of. This month is the 35th anniversary of a literary experiment by that delightful and inventive French writer, Georges Perec. In October 1974 he decided to station himself for three days in the place Saint-Sulpice in the posh 6th arrondissement of Paris in St Germain just north of the Jardin du Luxembourg and make a record of everything he saw. Tentative d'épuisement d'un lieu parisien (Attempt to exhaust all the possibilities of one particular spot in Paris) his little book is a record of what he saw. All those apple-green 2CVs, buses, Japanese tourists, aubergines (I'd forgotten that's French slang for a traffic warden), taxi-drivers, flâneurs, children, dogs, dossers passed by as he sat in cafés drinking coffee or vittel. Perec loved to tease out the poetry of the ordinary and what might sound like an exercise in obsessive tedium is in fact fascinating as we see a little quartier of Paris under the microscope. The artist, of course, sees what we don't always see and this is of course selective and proves that, in writing, the glory is in the detail and in what is selected rather than left out. This tiny book, with its occasionally glittering observations, has made my week, in that glum period after the clocks went back.

The media obsession with cultural anniversaries is not always complete – look how the books pages missed the fact that this year, nearly over, has been the centenary of Malcolm Lowry – but here's one you definitely haven't thought of. This month is the 35th anniversary of a literary experiment by that delightful and inventive French writer, Georges Perec. In October 1974 he decided to station himself for three days in the place Saint-Sulpice in the posh 6th arrondissement of Paris in St Germain just north of the Jardin du Luxembourg and make a record of everything he saw. Tentative d'épuisement d'un lieu parisien (Attempt to exhaust all the possibilities of one particular spot in Paris) his little book is a record of what he saw. All those apple-green 2CVs, buses, Japanese tourists, aubergines (I'd forgotten that's French slang for a traffic warden), taxi-drivers, flâneurs, children, dogs, dossers passed by as he sat in cafés drinking coffee or vittel. Perec loved to tease out the poetry of the ordinary and what might sound like an exercise in obsessive tedium is in fact fascinating as we see a little quartier of Paris under the microscope. The artist, of course, sees what we don't always see and this is of course selective and proves that, in writing, the glory is in the detail and in what is selected rather than left out. This tiny book, with its occasionally glittering observations, has made my week, in that glum period after the clocks went back.

Tuesday, 20 October 2009

Martina Evans: Facing the Public

I have just finished a fine new collection of poems by the Irish poet and novelist, Martina Evans, called Facing the Public and published by Anvil (£7.95). This is one of the best collections I have read for some time, drawing deep on her experience growing up in Ireland, the youngest of ten children, in a bar and shop in Cork in wonderfully deft and supple narratives. "These look like easy, anecdotal poems," Alan Brownjohn said of an earlier collection, "but they bite." That's certainly true of the new collection too – for beneath the swift-flowing narrative surface lie the raw anguish of childhood experience, and of family life, and the wider political legacy of sectarian and political violence. There's fine, dry humour here that suddenly lays bare the shock of raw experience or betrayal as when she tells of being invited to sit on the knee of a rather too friendly pseudo-progressive Franciscan at her boarding school: "I thought he was the liberated uncle I never had/so when he asked me to sit on his lap/I was genuinely sorry that I couldn't oblige." These are unillusioned pictures of Irish family life, with a sharp political perspective that is taken in by no one. Some of the short prose-poems made me impatient for more of those equally skilful and sharp-seeing novels like Midnight Feast that made Evans's reputation. "Tragedy and cheerfulness are inextricable," Bernard O'Donoghue has said about her poems. The mixture is compelling.

I have just finished a fine new collection of poems by the Irish poet and novelist, Martina Evans, called Facing the Public and published by Anvil (£7.95). This is one of the best collections I have read for some time, drawing deep on her experience growing up in Ireland, the youngest of ten children, in a bar and shop in Cork in wonderfully deft and supple narratives. "These look like easy, anecdotal poems," Alan Brownjohn said of an earlier collection, "but they bite." That's certainly true of the new collection too – for beneath the swift-flowing narrative surface lie the raw anguish of childhood experience, and of family life, and the wider political legacy of sectarian and political violence. There's fine, dry humour here that suddenly lays bare the shock of raw experience or betrayal as when she tells of being invited to sit on the knee of a rather too friendly pseudo-progressive Franciscan at her boarding school: "I thought he was the liberated uncle I never had/so when he asked me to sit on his lap/I was genuinely sorry that I couldn't oblige." These are unillusioned pictures of Irish family life, with a sharp political perspective that is taken in by no one. Some of the short prose-poems made me impatient for more of those equally skilful and sharp-seeing novels like Midnight Feast that made Evans's reputation. "Tragedy and cheerfulness are inextricable," Bernard O'Donoghue has said about her poems. The mixture is compelling.

Saturday, 17 October 2009

Is this It?

I step into Stanford's travel bookshop in Covent Garden and what do I see: I have finally become part of that doubtful company: the Three For Twos! The evidence is in this picture that my A Corkscrew is Most Useful: The Travellers of Empire (Abacus, 2009) is on the front table as part of a 3 for 2 promotion. 16 years after my first book was published I have finally crossed this Rubicon. Will life ever be the same again? Have I joined the fraternity of schlock? Well, not if being adjacent to Mark Mazower's Salonica is what it entails. I must digest this.

I step into Stanford's travel bookshop in Covent Garden and what do I see: I have finally become part of that doubtful company: the Three For Twos! The evidence is in this picture that my A Corkscrew is Most Useful: The Travellers of Empire (Abacus, 2009) is on the front table as part of a 3 for 2 promotion. 16 years after my first book was published I have finally crossed this Rubicon. Will life ever be the same again? Have I joined the fraternity of schlock? Well, not if being adjacent to Mark Mazower's Salonica is what it entails. I must digest this.

Tuesday, 13 October 2009

Elizabeth Bishop: A Poem to Wake Up To

One of the joys of having finally turned into my publisher a big non-fiction book is that I can return to poetry and I have just come across a glorious (untitled) poem by Elizabeth Bishop written some time in the late 1930s and published for the first time in Elizabeth Bishop: Poems, Prose and Letters which came out last year in the Library of America series.

One of the joys of having finally turned into my publisher a big non-fiction book is that I can return to poetry and I have just come across a glorious (untitled) poem by Elizabeth Bishop written some time in the late 1930s and published for the first time in Elizabeth Bishop: Poems, Prose and Letters which came out last year in the Library of America series.Tuesday, 29 September 2009

Lowry Ale in Liverpool

I have already written about the Malcolm Lowry Centenary Exhibition at Liverpool's Bluecoat Arts Centre but forgot to mention that there is a special ale (appropriate given Lowry's favourite leisure activity) brewed by the local Wapping microbrewery available in the Bluecoat bar . A crowded schedule prevented me from imbibing any of this ale at the opening night but I managed to snaffle an empty bottle whose contents had just been poured into the glass of the Bluecoat Director, Bryan Biggs (who drew the label) and here it is.

Wednesday, 23 September 2009

Win a Free Copy of de Bernière's New Book!

A free copy of Louis de Bernière's new collection of stories, Notwithstanding will be sent to the first person who identifies the location of this watercolour by Herbert Davis Richter R.I. (1874-1955) which my wife and I recently acquired. The painting is untitled and my guess is somewhere in Corsica but I could be wrong. It's a lovely picture and I'd like to know which waterside spot it represents. Thanks to Random House for the copy of the book.

A free copy of Louis de Bernière's new collection of stories, Notwithstanding will be sent to the first person who identifies the location of this watercolour by Herbert Davis Richter R.I. (1874-1955) which my wife and I recently acquired. The painting is untitled and my guess is somewhere in Corsica but I could be wrong. It's a lovely picture and I'd like to know which waterside spot it represents. Thanks to Random House for the copy of the book.

Monday, 14 September 2009

Manoly Lascaris, Partner of Patrick White

I have just received a fascinating book about Manoly Lascaris who was for many years the partner of the Australian novelist Patrick White. The book consists of records of the conversations its author, Vrasidas Karalis, associate professor in Modern Greek Studies at the University of Sydney, had over a seven year period as a young man with Lascaris, or "Mr Lascaris" as he insisted on being addressed. The conversations took place in Greek but the writing here in English is sharp and vivid. Vrasidas Karalis, whom I met in 2007 in Oxford when we were both delivering papers at a conference on Bruce Chatwin, is a very engaging, lively, and, on the evidence here, deeply tolerant thinker who put up cheerfully (mostly!) with the haughty patrician putdowns of Lascaris – who considered that he was descended from the Byzantine aristocracy. His bark, however, may have been worse than his bite and, in spite of his constant rebukes to his young interlocutor he clearly enjoyed the opportunity to talk about life and art in what is no less than a modern Socratic dialogue. One learns little about Patrick White, whom Vrasidas Karalis was translating at the time, and nothing about what Lascaris referred to as "the erotics" of his partnership with White, but it is a fascinating encounter with a provocative thinker who has previously not been allowed to come out from under the shadow of the Great Novelist. As Vrasidas Karalis says at one point: "Like Socrates, Lascaris was a wise old man who revealed unexpected truths through whimsical jokes and clumsy gestures." And again: "Manoly Lascaris never wrote anything, but he was a truly eloquent talker. He went directly to the heart of the matter, avoiding the periphrastic mannerisms of professional thinkers. He was a catalyst; his observations reduced everything to the basics." I strongly recommend this vigorous dramatic enactment of a surprising and unusual intellectual encounter.

I have just received a fascinating book about Manoly Lascaris who was for many years the partner of the Australian novelist Patrick White. The book consists of records of the conversations its author, Vrasidas Karalis, associate professor in Modern Greek Studies at the University of Sydney, had over a seven year period as a young man with Lascaris, or "Mr Lascaris" as he insisted on being addressed. The conversations took place in Greek but the writing here in English is sharp and vivid. Vrasidas Karalis, whom I met in 2007 in Oxford when we were both delivering papers at a conference on Bruce Chatwin, is a very engaging, lively, and, on the evidence here, deeply tolerant thinker who put up cheerfully (mostly!) with the haughty patrician putdowns of Lascaris – who considered that he was descended from the Byzantine aristocracy. His bark, however, may have been worse than his bite and, in spite of his constant rebukes to his young interlocutor he clearly enjoyed the opportunity to talk about life and art in what is no less than a modern Socratic dialogue. One learns little about Patrick White, whom Vrasidas Karalis was translating at the time, and nothing about what Lascaris referred to as "the erotics" of his partnership with White, but it is a fascinating encounter with a provocative thinker who has previously not been allowed to come out from under the shadow of the Great Novelist. As Vrasidas Karalis says at one point: "Like Socrates, Lascaris was a wise old man who revealed unexpected truths through whimsical jokes and clumsy gestures." And again: "Manoly Lascaris never wrote anything, but he was a truly eloquent talker. He went directly to the heart of the matter, avoiding the periphrastic mannerisms of professional thinkers. He was a catalyst; his observations reduced everything to the basics." I strongly recommend this vigorous dramatic enactment of a surprising and unusual intellectual encounter.Thursday, 10 September 2009

Who's Afraid of Malcolm Lowry?

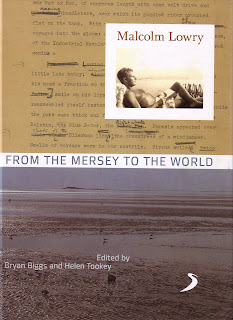

2009 is the centenary of the birth of Malcolm Lowry but you could be forgiven for not knowing this fact as it has attracted little attention so far. But a new book by many hands, Malcolm Lowry: From Mersey to the World is just about to be published by Liverpool University Press and there's an accompanying exhibition opening at the Bluecoat Arts Centre in Liverpool on 24th September when the book is launched. I have contributed a chapter on October Ferry to Gabriola with an autobiographical introduction explaining my choice of this, probably one of Lowry's lesser read works. There are lots of essays by a very varied cast of contributors under the helmsmanship of Bluecoat Director Bryan Biggs and Helen Tookey so don't delay!

2009 is the centenary of the birth of Malcolm Lowry but you could be forgiven for not knowing this fact as it has attracted little attention so far. But a new book by many hands, Malcolm Lowry: From Mersey to the World is just about to be published by Liverpool University Press and there's an accompanying exhibition opening at the Bluecoat Arts Centre in Liverpool on 24th September when the book is launched. I have contributed a chapter on October Ferry to Gabriola with an autobiographical introduction explaining my choice of this, probably one of Lowry's lesser read works. There are lots of essays by a very varied cast of contributors under the helmsmanship of Bluecoat Director Bryan Biggs and Helen Tookey so don't delay!

Wednesday, 9 September 2009

John Banville in Bloomsbury

Wednesday, 26 August 2009

Summertime: the New Coetzee

From time to time some under-employed journalist writes one of those standard pieces about what is wrong with the contemporary novel and the diagnosis is always the same: let us have a grand state-of-the-nation panorama and all will be well in the best of all possible worlds. I gather that, even as I speak, Sebastian Faulks has obliged. I have never been convinced by this to-hell-with-Dostoevsky-let-us-have-Trollope thesis. I think the art of fiction is different from documentary and that the difference matters.

From time to time some under-employed journalist writes one of those standard pieces about what is wrong with the contemporary novel and the diagnosis is always the same: let us have a grand state-of-the-nation panorama and all will be well in the best of all possible worlds. I gather that, even as I speak, Sebastian Faulks has obliged. I have never been convinced by this to-hell-with-Dostoevsky-let-us-have-Trollope thesis. I think the art of fiction is different from documentary and that the difference matters.Thursday, 20 August 2009

Kate Pullinger: The Mistress of Nothing

Tuesday, 18 August 2009

Pietro Grossi: An Interview

Bibliophilic Blogger hosts its first ever Virtual Book Tour. Scary!

Pietro Grossi's second book Fists, first published in Italian as Pugni in 2006 and now receiving its first English language publication by Pushkin Press, translated by Howard Curtis, has won great acclaim in Italy, winning many distinguished literary prizes. It consists of three novellas, all of which explore male rites of passage into adult life. The first story, “Boxing”, is about the confrontation between two young boxers who learn the hard way that life is about winners and losers, the second, “Horses, is about two brothers exploring the adult world together through the world of horses, and the third, “Monkey” is about a young man whose friend withdraws from life and starts behaving like a monkey, an unsettling experience that forces him to evaluate his own life and values. These three narratives are spare and swift and compelling and the influence of American masters like Hemingway has been noted by critics.

Pietro very kindly agreed to be interviewed by email in English by the Bibliophilic Blogger.

B.B: It seemed to me that this was a very masculine book in the sense that women hardly feature in the first two stories and when they do assume a larger role in the third story the male characters are not entirely at their ease with them. Nor are they free from some rather old-fashioned macho ideas – assuming a woman's difficult behaviour in one case proceeds from premature menopause, for example. And there's that rather shocking sentence about a woman film agent:"She was one those overweight women with their wombs full of cement who at some point in their lives have decided that a good business deal is better than sleeping with a man." [p121] Was this deliberate,? It is clear that each of the three stories is in some sense an exploration of the male rite of passage but were you also trying to conduct an implicit critique of masculinity?

PG: My grandparents, on my mother's side, gave life to a 65 person family, still increasing. Most of them are females. I just think that in my book I was trying to forget women. Joking apart, I found out along the way that my stories have a deep connection with my dreams, more than with my life. In this sense I am sure that the main characters of Fists are all people that somehow or another I dreamt of being. I would have loved to live their experiences, have their guts or their will or their talent or their madness. And yes, also the opportunity to simply live their changes as young men, with all its power and its loneliness. An older Italian author once, presenting me and my book at a festival, said that he loved “Boxing” so much because he thought it was mainly a duel story and that in duels – when it's a duel between men – women have to be

left aside. I remember smiling when he said this. Anyway, to be honest, I don't know: most of my stories come out in their own way and once they are written I just can sit there and read them like anyone else. Then think about what I read and decide if keep it as it is or not. Women weren't there that much and I guess I simply didn't miss them.

B.B: You have expressed your imagination for Salinger and Hemingway and Italian critics seem to have concentrated on the influence on your writing of various other American authors, but what of European authors? Which do you admire? And which Italian authors?

P.G: When you start talking about literature it is always difficult – if not impossible – to compress in a bunch of seconds or a bunch of words all the books and the authors you loved and who influenced you and your life and your writing. This is why next to my name always popped out American authors: because, at least for the moment, if I have to highlight the literature that mostly influenced me it is definitely 20th century North American literature. Having said that, there are endless European authors that made the man and the author I am: Tolstoy, Dumas, Svevo, Pirandello, Conrad, Austen, Shakespeare, Dante, Hesse... The list is so long that I really wouldn't know where to start from, and to be honest the greatness of these authors is so huge that to me talking about them is very difficult: it would be like a sailor trying to explain the importance of wind.

B.B: You are evidently attracted to the shorter novella form. Is this more congenial to you? Are you tempted by the idea of a longer novel?

P.G.: Yes, apparently for the moment novellas are a lot more congenial to me. Which wouldn't be a big problem if I was one of those people who love to sit on what they are good at. Sadly I am not that kind of person, so I keep on trying to write longer and more complex stories, which intrigue me a lot more but for the moment don't come out as smooth. The book I published after Fists is actually a longer story (not really a novel by my point of view) and among other things I am working now on a book that could probably be the closest thing to a novel I ever wrote.

B.B: Stylistically you prefer a relatively spare, unadorned style. Is this simply a matter of personally feeling more comfortable with that way of writing or are you reacting in any sense against prevailing styles in contemporary Italian fiction?

P.G. I think I am just reacting against what is going on inside my own head. As a kid I was very presumptuous and thought that I had some very good ideas about the world and all its matters. Than I realized that my ideas weren't that bright, they were just complicated. So I tried to write without thinking and things came out much smoother: everything was very simple and the world appeared like a pretty nice place. I thought I could live with that for a while.

B.B: The translation of your book by Howard Curtis reads very well and is very pacy. Do you have any apprehensions about being translated? Do you fear that something can be lost in the process?

P.G: No, not really. I don't want to sound immodest but I don't feel any apprehension about being translated. I have translated some books myself and I know that something is always lost. Something else, on the other side, is found. I just think that translated books are somehow different animals and have to be read in a different way: they will probably find different kinds of readers and give slightly different emotions. This anyway happens to every reader: the story is somehow told to me by the narrator, I put it on paper the best I can, then I start reading it and I discover a lot of surprising things I had no idea about; then somebody publishes it and thousands of other people read it and find thousands of other surprising things. I guess this is just the whole big magic about literature.

B.B: What are you working on now?

P.G: I am as always working on different things. I write my first draft by hand and without thinking about anything, then some time or another I have to bring the story to the computer and start thinking about it. So it ends up I am always working on two or three different things, at different stages. Lately I am mostly working on the book I was previously talking about, my probable next novel. If it will keep the way it is it will be pretty different from the way I have been working till now, so I am very excited and very anxious. Anxiety pills work very well.

B.B: In the UK, notoriously, fewer European authors are translated than in any other European country, and in Italy there is probably more curiosity about foreign writers. Which contemporary British writers interest you?

P.G: At the top of my list I have to put Nick Hornby, especially High Fidelity. I have no idea how he is seen in the UK but I definitely would have never written the way I write if I hadn't read the book four or five times. Its wit and its simple style struck me at the time. Then probably, out of all, the two authors I find most interesting are Zadie Smith and Martin Amis. The latter's The Information is probably one of the most important European books of the past twenty years, at least for an author.

B.B: Thank you Pietro, and thanks to Pushkin Press.

For details of the Virtual Blog Tour see:

August

Wednesday 19th Alma Books Bloggerel http://www.bloggerel.com

Thursday 20th Bibliophilic Blogger http://bibliophilicblogger.

Friday 21st Nihoni Distractions http://nihondistractions.

Monday 24th The Truth About Lies http://jimmurdoch.blogspot.com

Tuesday 25th Pursewarden http://pursewardenblog.

Wednesday 26th The View From Here http://www.

Thursday 27th Bookmunch http://bookmunch.wordpress.com

Friday 28th Notes in theMargin http://christopherschuler.

September

Thursday 3rd Lizzy’s Literary Life http://lizzysiddal.wordpress.

Thursday, 6 August 2009

I Remember, I remember

Remember the 1980s? Remember feminism? Remember 'gender-specific language'?

Remember the 1980s? Remember feminism? Remember 'gender-specific language'? Tuesday, 4 August 2009

An Instant Poem

A Wish

Outside the Library in Euston Road

a girl is running in a shower of rain;

on the taut canopy of her umbrella

the multi-coloured letters spell:

PLEASE RAIN ON ME.

In the long dampness of an English summer,

may her wish be granted.

Monday, 3 August 2009

Blogging and the Real World

Tuesday, 28 July 2009

At the Bright Hem of God: Radnorshire Pastoral by Peter J Conradi

At the Bright Hem of God: Radnorshire Pastoral

by Peter J Conradi

Seren, £9.99. 240pp

The last dragon in Wales sleeps in the Radnor Forest – a seven mile long upland area of East Wales that most Independent readers would understandably be unable to pinpoint on a map. The creature will not wake so long as he remains ringed by the multiple churches of the dragon-slayer, St Michael (Llanfihangel). In the lee of one such church, at the end of a two and a half mile hedged cul de sac, and itself ringed by 1000-year-old yews in a circular churchyard (the devil enters at corners) lives Peter J Conradi, a mild-mannered Prospero summoning up the benign spirits of Radnorshire past: writers, poets, historians, anchorites and mystics.

Conradi is alive to the magical and other-worldly dimension of the hauntingly beautiful Welsh March – the Elizabethan magician, Simon Dee may have been born here – but this is not a flaky or New Age treatise – and he acknowledges the mixed benefits of the incomer invasions which somehow have never swamped the locals, whose characteristic speech patterns, weathered obliquity, and gift for slow living he captures well. He is also keen to refute the idea that this is some sort of anglicised margin rather than, as he contends, a central repository of the true spirit of Welshness since the 12th century. He presents in sequence writers like Gerald of Wales, a suitably mongrel Welsh/Norman border figure, the poets Herbert, Traherne, Vaughan who sought and found “the Paradise within” in this numinous landscape, the attractive figure of the Reverend Francis Kilvert whose humane curiosity and kindness appeal to him and who provokes one of his rare personal lyric flights. There is Chatwin of course, and a contemporary trio of poets, R.S.Thomas, Roland Matthias, and Ruth Bidgood who have celebrated what Conradi calls 'the March', an area he has known for 40 years. Wales “has absorbed many English enthusiasts for its scenery and history: it can in me find room for one more”.

Generally, Conradi doesn't thrust himself on the reader, and writes a thoughtful and non-judgemental prose even when dealing with what have been highly contentious matters of Welsh politics and cultural identity. He judges (in a gentle slight to the more famous Thomas) R.S. Thomas (who supplies the book's title) to be the greatest 20th century Welsh poet writing in English but is unillusioned about what he calls tactfully, Thomas's “human frailties”. He is glad to quote Bidgood's declaration that she did not come to this area to escape the world: “This is the world.”

Conradi has written the perfect primer to this quiet stretch of Wales and Simon Dorrell's exquisite pen and ink miniatures complete what must be the best introduction to this area ever written.

Nicholas Murray's Bruce Chatwin (1993) is to be re-issued later this year.

Monday, 13 July 2009

Can Anyone Save Publishers from Themselves?

Contemplating (above) the fresh honeysuckle in my Radnorshire garden I try to hold on to some sanity in a world where publishing seems intent on a course of wild self-destruction. In today's Independent a two-page spread with a silly heading: "Two Weeks to Save Britain's Book Trade" attempts to say what is wrong with the business [meaning: the big hitters like Coetzee will all be published in our equivalent of the French rentrée littéraire in September in a two week period hoping to stem the losses so far this year being incurred by publishers]. Conventional wisdom says that publishing always rides the recession but this time it isn't happening and sales have slumped. Publishers are sacking their staff, advances are crashing down and things, as this blog has been saying for some time, are looking very grim indeed. Even Richard and Judy seem to have retired from the fray. In this article, however, one ray of light shines out. Someone actually enunciates a simple but incontrovertible truth about how we got into the mess that is contemporary British publishing. Step forward Jonny Geller, managing director of the books division of the Curtis Brown literary agency who tells it like it is: "Publishing has become quite reactive. It is sales-led. We need publishers to start taking risks again." He is saying that publishers should become publishers again. Give that man a gong.

Contemplating (above) the fresh honeysuckle in my Radnorshire garden I try to hold on to some sanity in a world where publishing seems intent on a course of wild self-destruction. In today's Independent a two-page spread with a silly heading: "Two Weeks to Save Britain's Book Trade" attempts to say what is wrong with the business [meaning: the big hitters like Coetzee will all be published in our equivalent of the French rentrée littéraire in September in a two week period hoping to stem the losses so far this year being incurred by publishers]. Conventional wisdom says that publishing always rides the recession but this time it isn't happening and sales have slumped. Publishers are sacking their staff, advances are crashing down and things, as this blog has been saying for some time, are looking very grim indeed. Even Richard and Judy seem to have retired from the fray. In this article, however, one ray of light shines out. Someone actually enunciates a simple but incontrovertible truth about how we got into the mess that is contemporary British publishing. Step forward Jonny Geller, managing director of the books division of the Curtis Brown literary agency who tells it like it is: "Publishing has become quite reactive. It is sales-led. We need publishers to start taking risks again." He is saying that publishers should become publishers again. Give that man a gong.

Friday, 3 July 2009

Tsvetaeva in Pimlico: Russian Poetry at the Tate

Thursday, 2 July 2009

Some Heatwave Recommendations

It must be the heat – over 30 degrees today in London – that is slowing down the blogbrain but I seem to be writing less here these days. Here, however, are two recommendations following people kindly sending me copies of their publications. The first is the latest issue of The Reader. This is a very nicely produced magazine with an odd title and the issue I have been sent has articles on Milton (see right), poems, fiction extracts, celebrity columns (Ian McMillan etc) and reviews. And what's more it originates from my old university Department of English at Liverpool.

It must be the heat – over 30 degrees today in London – that is slowing down the blogbrain but I seem to be writing less here these days. Here, however, are two recommendations following people kindly sending me copies of their publications. The first is the latest issue of The Reader. This is a very nicely produced magazine with an odd title and the issue I have been sent has articles on Milton (see right), poems, fiction extracts, celebrity columns (Ian McMillan etc) and reviews. And what's more it originates from my old university Department of English at Liverpool.Wednesday, 24 June 2009

New Music at the War Museum

To the Imperial War Museum last night for a fine concert of newly commissioned pieces for strings played exquisitely by the Solaris Quartet. The Museum decided to launch a Young Composer Competition with the commission to write a piece prompted by the current "In Memoriam" exhibition at the Museum until September.

To the Imperial War Museum last night for a fine concert of newly commissioned pieces for strings played exquisitely by the Solaris Quartet. The Museum decided to launch a Young Composer Competition with the commission to write a piece prompted by the current "In Memoriam" exhibition at the Museum until September. Tuesday, 16 June 2009

Marbles and the Cultural Elite

I have been a very dilatory blogger recently (reading too many damned books) but I am forced to write today having read a piece by Stephen Moss in this morning's Guardian about the Parthenon/Elgin marbles. A spokesperson for the British Museum is quoted and one can hear the fluting tone in this spectacularly arrogant piece of nonsense: "In Greece the sculptures can be viewed as part of the history of Athens and the Acropolis; here, they can be seen as part of a world history." Where does one begin to respond to such clottish impertinence?

I have been a very dilatory blogger recently (reading too many damned books) but I am forced to write today having read a piece by Stephen Moss in this morning's Guardian about the Parthenon/Elgin marbles. A spokesperson for the British Museum is quoted and one can hear the fluting tone in this spectacularly arrogant piece of nonsense: "In Greece the sculptures can be viewed as part of the history of Athens and the Acropolis; here, they can be seen as part of a world history." Where does one begin to respond to such clottish impertinence?Wednesday, 10 June 2009

Rupert Brooke And Other Matters

A blogless two weeks comes to an end as I return from 13 days drifting lazily through the Greek islands. I started at Skyros where Rupert Brooke ("some corner of a foreign field/That is for ever England") is buried in a solid marble tomb set in a local olive grove some distance from the shore but well known to the local (highly-priced) taxi drivers like Manolis who paces up and down having a fag while we pay our homage. Brooke's heroic patriotic stuff was written in the first phase of the Great War when this was what was wanted from the poets pre-Somme but actually he did not die like some Arthurian knight in the lust of battle (yes, my holiday reading included Malory's Morte d'Arthur) but from blood-poisoning from an insect bite on 23rd April 1915 the night before his fellow sailors left the island for the Dardanelles and the disastrous Gallipoli campaign. The bronze statue seen here of an "ideal poet" absurdly romanticises Brooke and it was interesting to discover that when it was unveiled in 1931 some of the locals were unhappy about its anatomical specificity.

A blogless two weeks comes to an end as I return from 13 days drifting lazily through the Greek islands. I started at Skyros where Rupert Brooke ("some corner of a foreign field/That is for ever England") is buried in a solid marble tomb set in a local olive grove some distance from the shore but well known to the local (highly-priced) taxi drivers like Manolis who paces up and down having a fag while we pay our homage. Brooke's heroic patriotic stuff was written in the first phase of the Great War when this was what was wanted from the poets pre-Somme but actually he did not die like some Arthurian knight in the lust of battle (yes, my holiday reading included Malory's Morte d'Arthur) but from blood-poisoning from an insect bite on 23rd April 1915 the night before his fellow sailors left the island for the Dardanelles and the disastrous Gallipoli campaign. The bronze statue seen here of an "ideal poet" absurdly romanticises Brooke and it was interesting to discover that when it was unveiled in 1931 some of the locals were unhappy about its anatomical specificity.Thursday, 21 May 2009

The Other Bloomsbury or H.D. in the Square

The Imagist poet H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) was also a novelist and I have just finished her roman à clef entitled Bid Me to Live, not published until 1960 but probably drafted in the late 1920s around the time her former husband, Richard Aldington, was writing his powerful and acerbic war novel, Death of a Hero (1929). Set in Bloomsbury in 1917-18, H.D.'s novel is a more subtle work of art and has the finely crafted patterning of a poem as it tries to capture the fragile mood of poets and painters and musicians in wartime London in Queen's Square (confusingly this is what she calls Mecklenburgh Square where she lived with Aldington while he was a soldier as there is also a Queen Square nearby). Thinly disguised pictures of these two plus Dorothy Yorke, D.H. and Frieda Lawrence ("Rico"), the composer Cecil Gray and Ezra Pound fill out a story of what used to be called 'free love' and higher Bohemian behaviour a little apart from the Big Guns of posh Bloomsbury not far away.

The Imagist poet H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) was also a novelist and I have just finished her roman à clef entitled Bid Me to Live, not published until 1960 but probably drafted in the late 1920s around the time her former husband, Richard Aldington, was writing his powerful and acerbic war novel, Death of a Hero (1929). Set in Bloomsbury in 1917-18, H.D.'s novel is a more subtle work of art and has the finely crafted patterning of a poem as it tries to capture the fragile mood of poets and painters and musicians in wartime London in Queen's Square (confusingly this is what she calls Mecklenburgh Square where she lived with Aldington while he was a soldier as there is also a Queen Square nearby). Thinly disguised pictures of these two plus Dorothy Yorke, D.H. and Frieda Lawrence ("Rico"), the composer Cecil Gray and Ezra Pound fill out a story of what used to be called 'free love' and higher Bohemian behaviour a little apart from the Big Guns of posh Bloomsbury not far away.Saturday, 16 May 2009

'I Am Just A Writer': Tahar Ben Jelloun in London

To the Institut Francais in London to hear the Moroccan novelist, Tahar Ben Jelloun, being interviewed by The Independent's literary editor, Boyd Tonkin about his latest novel to be translated (in French he's two books ahead of us). There were some jokes about the Englishing of Partir as Leaving Tangier – the Anglo-Saxons generally needing things to be laid on with a trowel (in this case through the name-check of a tourist destination) rather than putting up with the spare toughness of Partir. It's a novel about emigration set in the mid 1990s and couldn't be more relevant to these displaced, people-trafficked times. Tahar Ben Jelloun wryly observed that Moroccans wistfully stared at the lights of Spain, 14 kilometres away across the sea but he doubted that anyone from Spain gazed longingly in the other direction. The leading character of the novel, Azel, is a young Moroccan who sells his soul and body to get to Spain, away from a country that seems to offer him nothing. The author is unsparing in his candour about the shortcomings of Morocco in general and the Moroccan male in particular (he thinks it is the women who are its salvation) but admitted he had been criticised for "revealing" (he used the French verb dévoiler which has a nice extra nuance) too much in that regard but the European reader will learn a lot from this book. He also said that Europeans anxious about population movements in their direction might consider investing in Morocco so that people didn't have to leave. Tonkin asked if James Joyce had been a model as a writer and Tahar Ben Jelloun said that although when he was in prison and banned from reading and had asked his brother to smuggle in the fattest paperback he could find (which turned out to be a Livres de Poche translation of Ulysses) he felt Joyce was from a different world. At question time he was asked whether he saw himself as a Moroccan who happened to write in French and therefore part of "post-colonial literature" or a French writer. He smiled his charming smile and broke into English for the first time, giving his translator a rest: "I am just a writer".

To the Institut Francais in London to hear the Moroccan novelist, Tahar Ben Jelloun, being interviewed by The Independent's literary editor, Boyd Tonkin about his latest novel to be translated (in French he's two books ahead of us). There were some jokes about the Englishing of Partir as Leaving Tangier – the Anglo-Saxons generally needing things to be laid on with a trowel (in this case through the name-check of a tourist destination) rather than putting up with the spare toughness of Partir. It's a novel about emigration set in the mid 1990s and couldn't be more relevant to these displaced, people-trafficked times. Tahar Ben Jelloun wryly observed that Moroccans wistfully stared at the lights of Spain, 14 kilometres away across the sea but he doubted that anyone from Spain gazed longingly in the other direction. The leading character of the novel, Azel, is a young Moroccan who sells his soul and body to get to Spain, away from a country that seems to offer him nothing. The author is unsparing in his candour about the shortcomings of Morocco in general and the Moroccan male in particular (he thinks it is the women who are its salvation) but admitted he had been criticised for "revealing" (he used the French verb dévoiler which has a nice extra nuance) too much in that regard but the European reader will learn a lot from this book. He also said that Europeans anxious about population movements in their direction might consider investing in Morocco so that people didn't have to leave. Tonkin asked if James Joyce had been a model as a writer and Tahar Ben Jelloun said that although when he was in prison and banned from reading and had asked his brother to smuggle in the fattest paperback he could find (which turned out to be a Livres de Poche translation of Ulysses) he felt Joyce was from a different world. At question time he was asked whether he saw himself as a Moroccan who happened to write in French and therefore part of "post-colonial literature" or a French writer. He smiled his charming smile and broke into English for the first time, giving his translator a rest: "I am just a writer".Thursday, 7 May 2009

Exercises in Style: Raymond Queneau

Reading John Calder's obituary of the translator Barbara Wright in today's Guardian co-incided with the arrival in the post of a review copy from One World Classics of her translation of Raymond Queneau's Exercises de style (1947) which she translated first in 1958 and then re-issued in 1979 for John Calder but which is re-issued once more in a revised translation by One World at £7.99. In his obituary Calder describes Exercises in Style as "the banal story of a minor incident on a bus, told in 99 different ways". Queneau's madcap inventiveness must have created many headaches for the translator but Calder continues: "The author encouraged her invention of new English equivalents for those chapters that were too embedded in idiomatic French to be transcribed. A working relationship was established and she went on to translate many of Queneau's works." Wright's Cockney version of the story (one of the 99) is a tour de force and very funny. Highly recommended – as is One World's blog. One World have acquired John Calder's backlist and therefore there are lots of pleasures to come.

Reading John Calder's obituary of the translator Barbara Wright in today's Guardian co-incided with the arrival in the post of a review copy from One World Classics of her translation of Raymond Queneau's Exercises de style (1947) which she translated first in 1958 and then re-issued in 1979 for John Calder but which is re-issued once more in a revised translation by One World at £7.99. In his obituary Calder describes Exercises in Style as "the banal story of a minor incident on a bus, told in 99 different ways". Queneau's madcap inventiveness must have created many headaches for the translator but Calder continues: "The author encouraged her invention of new English equivalents for those chapters that were too embedded in idiomatic French to be transcribed. A working relationship was established and she went on to translate many of Queneau's works." Wright's Cockney version of the story (one of the 99) is a tour de force and very funny. Highly recommended – as is One World's blog. One World have acquired John Calder's backlist and therefore there are lots of pleasures to come.Wednesday, 6 May 2009

Leaving Tangier: Tahar Ben Jelloun in London

The Moroccan novelist Tahar Ben Jelloun will be in London next week at the Institut Francais talking with Independent Books Editor, Boyd Tonkin, about his latest book to be translated into English by Linda Coverdale, Leaving Tangier. I look forward to reading this new book from the excellent Arcadia books and have been preparing myself by finishing his searing and brilliant earlier novel This Blinding Absence of Light/Cette aveuglante absence de lumière (2001) which was also translated by Linda Coverdale. More next week after the event on Friday 15th May at the Institut Francais (tickets £5).

The Moroccan novelist Tahar Ben Jelloun will be in London next week at the Institut Francais talking with Independent Books Editor, Boyd Tonkin, about his latest book to be translated into English by Linda Coverdale, Leaving Tangier. I look forward to reading this new book from the excellent Arcadia books and have been preparing myself by finishing his searing and brilliant earlier novel This Blinding Absence of Light/Cette aveuglante absence de lumière (2001) which was also translated by Linda Coverdale. More next week after the event on Friday 15th May at the Institut Francais (tickets £5).

Friday, 1 May 2009

Off with Their Heads or Advice to the New Poet Laureate

Thursday, 30 April 2009

London's Second Hand Bookshops: No 2

Continuing my occasional series about the vanishing species of second hand bookshops, this is the Marchmont Bookshop at 39 Burton Street London WC1 (0207 387 7989.) It's the nearest to the British Library (if you discount the remainder shops) and is tucked away behind Cartwright Gardens. Those trays you can see outside often turn up literary gems. Just now I was tempted by the first Penguin edition of William Golding's Pincher Martin at £2.50 until I remembered I already had a copy. Inside, the emphasis is mostly literary with a remarkable selection of 20th century poetry. This shop seemed to go very quiet a couple of years ago and I thought it was defunct but it is now trading regularly again and well worth a poke about. And it has the best wisteria of any bookshop in town.

Continuing my occasional series about the vanishing species of second hand bookshops, this is the Marchmont Bookshop at 39 Burton Street London WC1 (0207 387 7989.) It's the nearest to the British Library (if you discount the remainder shops) and is tucked away behind Cartwright Gardens. Those trays you can see outside often turn up literary gems. Just now I was tempted by the first Penguin edition of William Golding's Pincher Martin at £2.50 until I remembered I already had a copy. Inside, the emphasis is mostly literary with a remarkable selection of 20th century poetry. This shop seemed to go very quiet a couple of years ago and I thought it was defunct but it is now trading regularly again and well worth a poke about. And it has the best wisteria of any bookshop in town.

Thursday, 23 April 2009

Wales Book of the Year 2009

Tuesday, 21 April 2009

Beckett: Interim Thoughts on the Letters

Wednesday, 8 April 2009

William Gerhardie: the Pleasures of Accidental Discovery

When you are reaching the end of a long period of research on a book with masses of highly-targeted reading, it's one of life's great pleasures to discover when you were least expecting it, something absolutely new and unexpected and gratuitous.

When you are reaching the end of a long period of research on a book with masses of highly-targeted reading, it's one of life's great pleasures to discover when you were least expecting it, something absolutely new and unexpected and gratuitous. Sunday, 5 April 2009

London's Second Hand Book Shops: No 1

Although websites like Abe Books have transformed the way in which we track down out of print books (you can find virtually anything without leaving home) some of us still get pleasure out of browsing and making unexpected discoveries in real bookshops. In Central London there are still some interesting and quirky shops, though they are gradually disappearing. In the first of an occasional series I want to start with one of my favourites, Walden Books, in Camden. Not quite "Central London" but easily accessible by a 168 bus from Bloomsbury to Chalk Farm, Walden Books in Harmood Street has a profusion of quality books for the literary forager. It has a fantastic collection of Penguins classic and modern, and lots of literary criticism, poetry, and biography, and is just the place to go for a cheap reading edition of your favourite Tolstoy or Graham Greene or less well known 20th century writers in English or in translation. The only downside is that, as you can see, a lot of the stock is kept outside and shows the effect of the weather sometimes, but it has a proprietor who understands the insides of his books and everything is reasonably priced. Long may it survive, but remember it's only open Thursday to Sunday.

Although websites like Abe Books have transformed the way in which we track down out of print books (you can find virtually anything without leaving home) some of us still get pleasure out of browsing and making unexpected discoveries in real bookshops. In Central London there are still some interesting and quirky shops, though they are gradually disappearing. In the first of an occasional series I want to start with one of my favourites, Walden Books, in Camden. Not quite "Central London" but easily accessible by a 168 bus from Bloomsbury to Chalk Farm, Walden Books in Harmood Street has a profusion of quality books for the literary forager. It has a fantastic collection of Penguins classic and modern, and lots of literary criticism, poetry, and biography, and is just the place to go for a cheap reading edition of your favourite Tolstoy or Graham Greene or less well known 20th century writers in English or in translation. The only downside is that, as you can see, a lot of the stock is kept outside and shows the effect of the weather sometimes, but it has a proprietor who understands the insides of his books and everything is reasonably priced. Long may it survive, but remember it's only open Thursday to Sunday.Friday, 27 March 2009

Sweetness and Light:Matthew Arnold In Japan

Thirteen years after its first UK publication, my biography of Matthew Arnold has just appeared in Japanese which raises the interesting question of how he is seen in Japan today. Perhaps someone will let me know. Often seen in Britain in caricature as an "élitist" who defined culture as "the best that has been thought and said in the world", Arnold in fact remains an interesting and relevant thinker. If his detractors just read his two essays, "Democracy" and "Equality" they would see an utterly different Arnold from the bewhiskered "elegant Jeremiah" attacked by one of his contemporaries. And his belief that inequality damages everyone not just the disadvantaged is the theme, if I am not mistaken, of a much-praised book on equality published this month.

Thirteen years after its first UK publication, my biography of Matthew Arnold has just appeared in Japanese which raises the interesting question of how he is seen in Japan today. Perhaps someone will let me know. Often seen in Britain in caricature as an "élitist" who defined culture as "the best that has been thought and said in the world", Arnold in fact remains an interesting and relevant thinker. If his detractors just read his two essays, "Democracy" and "Equality" they would see an utterly different Arnold from the bewhiskered "elegant Jeremiah" attacked by one of his contemporaries. And his belief that inequality damages everyone not just the disadvantaged is the theme, if I am not mistaken, of a much-praised book on equality published this month.