"A precondition for reading good books is not reading bad ones: for life is short" - Schopenhauer.

Wednesday, 5 October 2022

The Prime Minister Regrets by Nicholas Murray

Tuesday, 13 September 2022

Writing Material

Does it matter what one writes with? Creative writing tutors have their endearing prohibitions and recommendations (write about what you know, don’t use adjectives etc etc) but the physical medium of writing itself tends to be dismissed as nothing more than an irrelevant personal quirk that has little bearing on what gets written.

But does it? Iris Murdoch famously preferred to write in fountain pen (“One should love one’s handwriting”) and the mystic union of hand and writing instrument (quill or MacBook) should not, perhaps, be too quickly dismissed. In a similar way, on a writer’s desk a pebble from a Greek beach, a statuette, a piece of coloured glass, can be the crucial co-ordinates of creativity, aids to the chancy manoeuvres of composition.

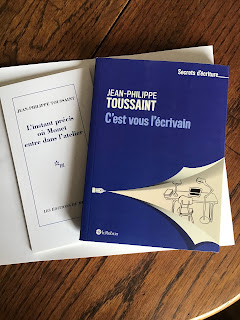

A new book from the French writer Jean-Philippe Toussaint, C’est vous l’écrivain (You are the Writer) takes it title from a remark offered to Toussaint when his first novel was accepted by the legendary Jerome Lindon of Éditions de Minuit, publisher of the nouveau roman of the 1950s. The fledgling author timorously offered Lindon a list of post-acceptance alterations and second-thoughts, fearing that this would be taken wrongly but Lindon coolly replied: “c’est vous l’écrivain,” with the unspoken warning, however, that the writer might propose but, as fearsome editor, obsessed with detail, Lindon’s scalpel would not stay long in its sheath.

Toussaint describes in fascinating detail his own writing methods, the succession of Apple computers he has worked on, each page printed off for intense reworking with a hand-held pen, fonts played with, patterns of text laid out on the page for evaluation (he prints a bizarre example of cramped micro-paragraphs arranged like troops at a dictator’s victory parade), dictionaries ransacked, everything subjected to forensic re-writing. Not for him the astonishingly rapid productivity of Stendhal who could hardly have had time to check for a missed comma (The Charterhouse of Parma’s 500 pages tossed off in 53 days).

Ford Madox Ford, in his characteristically digressive memoir/fiction It Was the Nightingale (1934) confessed that he disliked writing with a pen, in part because of arthritic pain. He was forced to use a new Corona typewriter and even tried dictation to a stenographer – but this made it all too easy: “If I have to go to a table and face pretty considerable pain I wait until I have something worth saying to say it in the fewest possible words.” Ford had put his finger on a crucial need for any writer: to have an invisible antagonist to wrestle with. If it isn’t the product of sweat and toil it has come too easily. Unlike the computer which has made rewriting and re-positioning text so effortless, Ford found insupportable the typewriter’s requirement for him to redo a whole page in order to eliminate a mistake (“I detest a typewriter page showing any corrections”). He went to extraordinary lengths to avoid having to retype, even finding a new context in the words around it for the mistaken word in such a way that it now worked without alteration. But he knew the ultimate truth: “Elimination is always good.”

In the end Ford Madox Ford resolved to return to writing with a pen. His advice to any writer was “in composing make your circumstances as difficult as possible” but erase any mistakes with “bold, remorseless black strokes”.

For Jean-Philippe Toussaint, who began with an Apple LC2 in 1993, and has passed through every ordinateur portable from that stable since then, these years have seen “a silent revolution” in the processing of words which he judges nonetheless as “a natural evolution of the practice of writing” leaving him, however, to speculate about what communications revolution is waiting for his old age.

For my own part, I am grateful that I never learned to touch type, my two-fingered dexterity being quite fast enough, if not quite Stendhalian. As I watch the fingers of others flick like lightning over the keyboard I am relieved that I cannot go any faster. I know that slowness is good for me, hauling me back from the precipice of a too-fluid sentence. As Ovid urged, in another context, lente, lente, currite noctis equi.

But strictures about writing will always retain a certain specious logic. What looks like a rule, a necessity, a universal truth, will turn out to be merely a piece of advice that might work for you but not necessarily for me. Closer to a lucky charm than a law of physics, these strictures aid us in the good work of being hindered, help to convince us that we are on the stony but right track.

The only immutable law, however, remains the one that should be carved into the marble lintel of every writing school: all writing is re-writing.

Monday, 5 September 2022

Friday, 22 July 2022

Bookbrowsing

Buying books online – though fast, effortlesss and efficient – cannot offer the same serendipitous pleasures of accidental discovery, the gleeful snatch from the shelf of a palpable bargain. In the estimable Cinema Bookshop at Hay-on-Wye recently the four volumes of the beautiful Nonesuch “Coronation Edition” of Shakespeare’s works of 1953 in tip-top condition in a battered slipcase offered themselves at £40, a tenner for each volume. Notwithstanding the line-up of annotated Arden editions at home who could resist such a lovely reading copy on delicate India paper? Or was it the thought of a bargain, confirmed by the flutter to the floor from between the pages of The Merry Wives of Windsor of an invoice for its last change of hands at a posh Mayfair antiquarian book dealer for £130?

Browsing in bookshops is one of those visceral pleasures that has nothing to do with logic or efficiency. In a real shop, too, one at least can handle the real thing and not be disappointed by the arrival of a book that wasn’t what one wanted and turns out to be an ex-library book (that condition not always signalled by the less scrupulous dealers – though I am rather fond of my copy of Eric Auerbach’s classic Mimesis with its big black stamp from Grimsby Public Libraries). Secondhand books come into your hand in all their tactile, olfactory immediacy. You know what you are getting. And online booksellers vary considerably in the accuracy (and honesty) of their sales descriptions. Some, the so-called “bookjackers”, don’t even hold what they advertise (sourcing it later) in order to hook in customers through an obscure manipulation of the process that others will understand better than I.

There is also the pleasure of outwitting the system. Did Oxfam in Leominster really mean me to get an immaculate first edition of Wyndham Lewis’s Blasting and Bombadiering for only £3? Oxfam shops all have their “antiquarian” section which in my experience means “distinctly tatty overpriced older books” – but the word “Oxfam” is better passed over when in the company of independent booksellers who resent its free stock acquisition and prime high street locations which have forced some traditional shops to close.

Online bookselling has probably ended the era of romance in bookselling, dispelling the mystifications of a world once described by Iain Sinclair in an interview as “a masonic society” – which probably reached its apogee in the enigmatic figure of Drif, author of the splendidly opinionated and often downright abusive (and out of print) Drif’s Guide to the secondhand and antiquarian bookshops in Britain. Drif even appears as a fictional character, Dryfeld, in Sinclair’s 1987 novel White Chappel, Scarlet Tracings (“Dryfeld sported a camelhair coat, with lumps of the camel still attached”). No one seems to know who Drif was, and the legends surrounding this sportive “book runner” (his collection of books on suicide, his ending his days in an asylum) are no doubt just that.

One of Drif’s wittier passages in a Guide that pulled no punches in attacking the often autocratic and customer-unfriendly behaviour of shops was his characterisation of the “roastbeef” end of the trade. This, he explained, meant “hearty, often stout books on hunting, shooting, fishing, polar exploration, fortification, toll booths, coaching inns, bees, clocks, windmills, Churchill, leather bottles, penny whistles, prisons, lazar houses etc etc”. How often has one stepped into such fussy mausoleums.

The internet, in short, is busy taking the quirkiness out of what is left of this putatively raffish business and if you are looking for an out of print book it makes sense, of course, to start with the used book websites, primus inter pares being bookfinder.com which lays out every available example of your sought title and tells you who is selling it and for how much.

Things turn out, however, to be not quite as simple as that.

I recently wanted to acquire a copy of Lorenzo in Taos (1933) by Mabel Dodge Luhan, having seen it feature first in Frances Wilson’s new life of D.H. Lawrence and then underpinning Rachel Cusk’s Booker-shortlisted novel Second Place. It’s out of print and the cheapest version one can acquire online is a print-on-demand new book from Woolf Haus Publishing at £19.99. If you wanted a first edition of the original hardback, probably in less than mint condition, you would expect to pay £40 or £50. Ruminating on these figures I stepped into the Blackheath Bookshop, a premises cruelly attacked thirty years ago by Drif, partly it seems because it looked out onto Blackheath “which is flat, featureless and fouled” which in turn “inspired the owner to make the bksp the same”. Perhaps under new ownership thirty years on, I found it a good enough browsing space and to my delight there was a copy of Mabel Dodge Luhan, the first UK hardback edition from Martin Secker priced at £12. I should add that it was in terrible condition, its spine flapping in the breeze and the binding battle-weary, but the text was clean and clear and it was the latter I was after. Application of some PVA adhesive and a dab or two of the trade’s Backus bookcloth cleaner (“apply with a soft cloth, lightly rubbing in all directions until the surface is evenly revived”) brought it almost back into respectability on my shelf.

The book also had the remnant of an owner’s bookplate and these can bring with them if not a backstory then some sort of intangible addition to the interest of a book. I have Lord Quinton’s New Lines, the classic anthology of Movement verse from 1956 in an excellent hardback first edition bearing his grand heraldic bookplate and (with a more modest signature merely) New Society editor Paul Barker’s copy of the Selected Poems (1968) of R.S.Thomas (acquired by me posthumously from Barker’s local Oxfam shop in Kentish Town). Both lightly handled.

Sadder perhaps, two volumes of the Muse’s Library edition of the poems of William Browne of Tavistock donated, says the bookplate, to Birmingham University Library by “Miss L.R. Lewis of Fairfield House, Redditch” in July 1939. She would have assumed that her gift to the university was an everlasting memorial but in the 1990s it was pitched into a crate and shipped off to Richard Booth’s bookshop in Hay where I would be waiting to retrieve it.

I continue to browse the bookshops, more now for the pleasure of accidental discovery than focussed search. They go on existing, like the alleged 18 miles of shelving of the Strand Bookstore in New York City (well, it certainly felt like that sort of distance last time I was there) or the more compact Capitol Hill Books in Washington DC (I left only with its pretty tote bag, not every visit to a bookshop resulting in a fresh catch). In the UK my favourites include Walden Books in Chalk Farm, Any Amount of Books in Charing Cross Road, or Ystwyth Books in Aberystwyth – outfits run by people who love books and have fresh stock flowing through. In Wantage, camouflaged by a second hand furniture shop, Regent Furniture shields a shop with – a fact that would astonish Drif – a helpful bookseller who bounded all over the shop with irrepressible enthusiasm looking (unsuccessfully) for the book I said I wanted. I lament the loss of the congested Gotham Bookmart on West 47th in Manhattan, of the Marchmont Bookshop in Bloomsbury with its rare poetry collection, and countless other small shops each with their quirky stock and often quirkier proprietor.

I have too many books and am currently weeding the shelves again, introduced only last week to a new app called Ziffit which involves pointing your phone at the barcode of each book until a basketful is priced up (very low prices given but I am just trying to clear space) and a courier arriving next day to bear it away for free. The rest goes to the charity shops, though during and after lockdown many were refusing to accept any more donations, overwhelmed by the lapping tide of printed and bound stuff.

My obsession with books began as a teenager in Liverpool, scanning the shelves of a second hand bookseller on the edge of Chinatown packed with the sort of bread-and-butter inexpensive classics I was beginning to discover at school and university. It was run by a man who always wore a distinctive short white jacket like that of a Cunard ship’s steward.

His name was Mr Waterston.

Friday, 15 July 2022

Elsewhere: The Collected Poems of Nicholas Murray

I am pleased to announce the publication of my Collected Poems, drawing together all my work to date. It is available from Melos Press where it can be ordered post-free or from here. It is called Elsewhere: Collected Poems of Nicholas Murray after one of the poems in that collection which talks of the contemplation of a painting taking us to “an exalted elsewhere”. This, it seems to me, is what the poetic imagination does: enhances reality (not encouraging us to ‘escape’ from it) transforming and sharpening perception. This is why the arts in general and literature in particular are so essential to human life. Without them we are denuded, less than complete.

Many of the poems are political, sometimes very unambiguously so in the vigorous political satires but sometimes much more obliquely, even invisibly so. And many of the poems are not the least bit political. I hope this makes for diversity and variety and I hope you enjoy the collection.

Here is what the publisher’s blurb says:-

Nicholas Murray’s many books include poetry, two novels, critically acclaimed biographies of Franz Kafka, Aldous Huxley, Bruce Chatwin, Andrew Marvell, and Matthew Arnold, and studies of Liverpool, Bloomsbury and British poets of the First World War. He is a Fellow of the Welsh Academy and, with his wife Sue, runs the prize-winning poetry imprint, Rack Press.

Nicholas Murray’s poems deal with love and art, humanity, politics, and the natural world in a body of work marked by both passion and fine craftsmanship. David Harsent has written that Murray has ‘a sure hand, whether with hard-edged satire...or sense impressions that produce place and event so vividly’

Praise for earlier collections of poems:

Of earth, water, air and fire ‘A real treat…an elemental menagerie in which the poet’s own delight through verbal magic becomes ours’. Christopher Reid

Get Real ‘A bravura display of finely controlled outrage.’ Times Literary Supplement

The Museum of Truth ‘A stunning collection.’ Martina Evans

City Lights ‘The poems have an emotional intelligence, a wit, that I really admire.’ Michèle Roberts